Sustainability Contested: Analysis of Stakeholders Participation in Municipal Solid Waste Management - A Case Study

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.3.27

Copy the following to cite this article:

Menon V. J, Palackal A. Sustainability Contested: Analysis of Stakeholders Participation in Municipal Solid Waste Management - A Case Study. Curr World Environ 2021;16(3). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.16.3.27

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Menon V. J, Palackal A. Sustainability Contested: Analysis of Stakeholders Participation in Municipal Solid Waste Management - A Case Study. Curr World Environ 2021;16(3). Available From: https://bit.ly/31jA3Fz

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 08-06-2021 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 02-12-2021 |

| Reviewed by: |

Grigorios Kyriakopoulos

Grigorios Kyriakopoulos

|

| Second Review by: |

Aparna Gunjal

Aparna Gunjal

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Umesh Chandra Kulshrestha |

Introduction

Across the globe, whether it is developed or developing countries, sustainable management of municipal solid waste (MSW) has always been a concern. Irrespective of the conventional approach of burying the waste without any systematic process, we need to adopt an integrated approach for achieving sustainability in municipal solid waste management (MSWM)1. Various factors such as the use of multiple collection and treatment options, the interconnection between different waste systems with other relevant systems (such as product design which could improve the scope of sustainability), and involvement of multi-stakeholders are necessary for developing a sustainable MSWM2.

Stakeholder participation, particularly involving communities could help in building local capacities and competencies. This could help to substantially improve the aptitude of local population to negotiate with authorities at the local body and thereby bringing in quality and responsible services to the ground such as better sanitation, drinking water and health services. Also, the involvement of multiple stakeholders in the decision-making process could ensure more effectiveness in grass-root level governance.

Looking through a social lens, stakeholder participation plays an effective role in sustainable MSWM as they include waste generators, waste managers and Government machinery. Integration of stakeholders into the waste management process, thus connecting their resources in order to develop a cooperative environment with a well-defined division of roles and responsibilities is an essential part of a sustainable MSWM3. Moreover, collective stakeholder participation, such as community involvement, could help in decentralizing MSWM, which has added benefits ranging from increased livelihood generation, health benefits (due to lack of huge structures or transportation aids for MSWM) and increased sense of ownership for the society4.

This paper discusses different dimensions of stakeholders’ participation in MSWM. It seeks to analyze the stakeholders’ role in MSWM through emphasizing its influence in two main approaches of MSWM, namely, centralization and decentralization, taking the case of Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation (TMC) in the State of Kerala, India.

The study has scrutinized the stakeholders’ participation in TMC’s MSWM; particularly the influence of community participation, involvement of NGOs and ground-level workers (contingency staffs as designated in TMC). In addition, the role of scrap workers and the influence of political leaders in TMC’s MSWM are also discussed.

Review of Literature

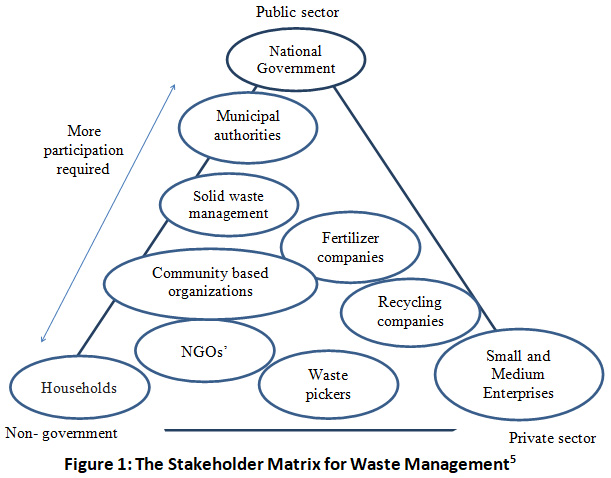

A sustainable process of MSWM needs partnerships, where multiple stakeholders need to be actively participating in the process. This integrates the societal and economic aspects of MSWM. Waste Concern’s model suggests that when multiple stakeholders are entering into a partnership model in MSWM (as seen in Figure 1), it could lead to sustainable profitable generation5. These inputs can be interpreted in a way that if the societal aspects and economic aspects are integrated along by considering the environment; the process of MSWM becomes sustainable.

|

Figure 1: The Stakeholder Matrix for Waste Management5. Click here to view Figure |

Usually, two approaches are seen for managing MSW around the world - centralized MSWM and decentralized MSWM. But, a mix of centralized and decentralized MSWM can also be observed. A centralized approach usually requires heavy infrastructure for the transfer and management of MSW, which requires more space and finance. Whereas decentralized MSWM required small infrastructures for the management of MSW; it also sees waste as a resource. Selection of approach should be made at the planning stage of MSWM itself by considering the local-level resources and responsibilities. For some cases; decentralized MSWM is suitable, such as for management of organic waste and for certain cases such as management of hazardous waste, biomedical waste and for recycling and recovery of inorganic materials centralized MSWM approach would be beneficial.6

Thus the selection of appropriate approaches needs to be carried out during the initial planning phase itself. When planning for an MSWM solution, often extensive attention is given to the up-gradation of technical specifications; but often, “general social and ecological goals” are being omitted7. Instead of going towards the exclusive technological up-gradation, if a social component of citizen participation is being brought in during the planning of MSWM, the overall approach shall become sustainable as it increases the citizen consciousness for environment awareness 8, 7.

Studies have reported some major contrasting differences between Centralized and Decentralized MSWM;

Table 1: The Main Differences Between Decentralized and Centralized Waste Treatment9

|

Centralized MSWM |

Decentralized MSWM |

|

Transportation costs relatively high |

Transportation costs relatively low |

|

Economies of scale non-adaptable to waste reduction |

The local matter is a local resource adaptable to the reduction |

|

Low-quality compost |

High-quality compost |

|

Need advanced technology |

Simple technology needed |

|

Large facilities |

Small facilities |

|

High treatment cost |

Low treatment cost |

One thing, which can be seen in the centralized MSWM approach is that the waste is normally being carried away from the city and altogether deposited in a specific location. As the amount of waste being brought is huge, the facility could endanger the ecological balance, social well-being and economic prosperity of the nearby area. Studies have reported that; usually areas where socially and economically backward people reside become the host location for centralized MSWM facilities. It can be seen as an example of discrimination and have led to many struggles 10, 11, 12.

Study Area and Context

TMC came into existence in the year 1940 and it now has 100 wards spread across 214.86 square kilometers (sq.km). According to the 74th constitutional amendment act and the Kerala municipalities act, 1994, the governance and administration of the TMC is vested with constitutionally elected corporation council13.

TMC has tried and tested both centralized and decentralized approaches for managing its municipal solid waste (MSW). A structured effort in TMC’s centralized MSWM was seen from the year 2000 onwards when Kerala’s first ‘centralized MSW treatment plant’ came into service at Vilappilsala; a small village situated in the outskirts of TMC. Unfortunately, TMC’s centralized MSWM initiative failed due to multiple reasons, ranging from faulty design of the ‘centralized MSW treatment plant’ to the lack of coordination in services14. Later on, an organized effort for decentralizing MSWM services was seen in TMC from 2014 onwards, i.e. after the closure of the TMC’s only ‘centralized MSW treatment plant’ at Vilappilsala.

Methodology

The study employed an interpretive paradigm and examined different dimensions of multi- stakeholders’ participation in MSWM, particularly with regard to its two main approaches - centralization and decentralization. A qualitative approach was primarily used for data collection and explored the role and influence of different stakeholders in the MSWM of TMC, in the past and present. Quantitative data collection was also conducted among 350 households of TMC to underline some of the findings obtained through qualitative data The main segment involved in the study is the households and other stakeholders of MSWM in TMC. Their influences during the centralization and decentralization phases of MSWM in TMC are being deliberated.

Eleven in-depth interviews were conducted with the stakeholders such as the common people, representatives of residents’ associations and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), technical experts from the field, contingency staffs of TMC, service providers, scrap workers, and political representatives, through engaging primarily with their experiences, knowledge and perceptions. Besides this, four FocusGroup Discussions (FGDs) were held, two of which were among the residential association members of TMC, the third one was among the households of a coastal slum in TMC and the fourth one was conducted at the Department of Sociology, University of Kerala. Apart from the on-field data collection, an extensive literature review was carried out to get an overall view on the topic of study and to substantiate the analysis of the data obtained from the ground.

TMC has a population of 957,730 which is spread across 214.86 square kilometers with 100 wards. The household size of TMC is 239,432 and for the study, 350 households were chosen for the quantitative survey through purposive sampling. The demographic profile of the sample chosen for the quantitative study is as follows;

Table 2: Gender of the Respondents.

|

Gender |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Female |

155 |

44.3 |

|

Male |

193 |

55.1 |

|

Prefer not to say |

2 |

.6 |

|

Total |

350 |

100.0 |

Table 3: Household Income Category of the Respondents.

|

Household Income Category |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

EWS |

81 |

23.1 |

|

HIG |

11 |

3.1 |

|

LIG |

119 |

34.0 |

|

MIG |

139 |

39.7 |

|

Total |

350 |

100.0 |

(EWS: Economically weaker section, HIG: High-income category, LIG: Low-income category, MIG: Middle-income category)

Table 4: Nature of the Residential Area of the Respondents.

|

Nature of the Residential Area of the Respondents |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

City center |

178 |

50.9 |

|

Coastal area |

7 |

2.0 |

|

Urban outgrowth |

56 |

16.0 |

|

Urban outskirts or suburb |

109 |

31.1 |

|

Total |

350 |

100.0 |

Results

Community Participation in Centralized MSWM Approach

It is widely discussed that the municipal bodies across the developing nations often fail in the implementation of successful MSWM programs due to the ‘collect, transport and throw away’ approach being followed. These types of conventional approaches are not designed on a need-based approach; instead, they follow a ‘one-size-fits-all approach’ which does not consider the community’s waste management requirements. Here, the ‘problem’ is that, waste is just being transferred from the point of generation to a disposal site. Thus, the responsibility is solely on the municipal authorities. Community members/neighborhood just plays the role of waste generators.15, 16

This problem generally replicates when a municipal body adopts a completely centralized approach for MSWM with the community as one of the stakeholders, is expected to play little role in the management activities. For example, in TMC’s centralized MSWM approach, it was extensively debated that the involvement of the community as one of the stakeholders was considerably less. A ‘consultant’ for TMC’s MSWM, opined that,

(…) During the centralization period, the residents were not expected to participate actively in municipal solid waste management. They just handed over whatever waste that was generated to the service providers. No segregation whatsoever was happening, also waste was considered as something untouchable. Naturally, the not in my backyard syndrome was present among the residents (…).

The MSWM consultant’s words clearly reveal the fact that the only responsibility of the TMC residents during the centralization of MSWM in TMC was handing over the waste to the service providers and that too was not properly carried out due to the negative attitude towards waste as something to be disposed of from one’s vicinity. This negative attitude towards waste led to ‘not in my backyard (NIMBY) syndrome. People affected by NIMBY will not allow their waste to be managed at the source, instead prefer that it be taken away from their backyard and be managed in a far-off area. Thus, they need not have to be concerned about the negative effects of the waste generated by them.

It is also reported in studies that in India, people generally have a negative perception towards solid waste management and it results in NIMBY syndrome, which leaves the responsibility of MSWM entirely in the shoulders of municipal bodies. This scenario results in a complete disruption of source-level segregation and mismanagement of MSW17.

Thus, during the time of the centralized MSWM Approach of the TMC’s MSWM scenario, there was no community involvement in the process and their role was just limited to waste generators.

Community Participation in Decentralized MSWM

An MSWM system is considered to be a continuous maintenance system, as continuous community participation is needed for the upkeep of the service and the system. This may include collection and segregation of waste and bringing the waste to a certain point and so on. Community participation, therefore, turns out to be a crucial aspect of any MSWM approach, which is more significant than any other municipal service as far as an urban setting is concerned3. However, only during recent years, the community participation component of MSWM got wider attention.

It is reported that, if a government or municipal bodies share the responsibility of MSWM among the community, the efficiency of the MSWM can be increased. Between 2003 and 2007, an NGO called ‘Toxic Links’, based in Delhi, initiated a decentralized community-based zero waste management project called ‘zero waste colonies’. It was implemented in multiple housing colonies, from low-income to high-income households. The NGO utilized vacant spaces within the colonies such as parks for setting up compost pits. The project was reported to be a success as a result of increased community involvement, which stimulated the source level management18. In TMC as well, community-oriented decentralized MSWM has brought about some visible changes. According to a former ‘executive director of Suchitwa Mission, Government of Kerala’,

(…) I would definitely say that there is a visible change in community participation through Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation’sdecentralized intervention. When comparing to the pre-Vilappilsala closure scenario, now the people in Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation’s are more aware of their responsibility towards municipal solid waste management. A major proportion of the population here has accepted the fact that their waste is their own responsibility. This can be observed by scrutinizing the number of households performing source-level waste management and comparing it with the previous scenario. Also, the number of people carrying their own carry-bags for shopping has increased about 40% when compared to pre-campaign period (…)

His observation affirms the notion that involving the community as one of the stakeholders in the process of MSWM will increase their responsibility towards the process. Moreover, the increased proportion of people carrying ‘own carry-bags’ for shopping indicates that sharing the responsibility of MSWM among people could result in waste reduction. The participants of FGD’s said that they practice re-using the carry bags, which they already have with them.

Table 5: Source Level Segregation of MSW among Households in TMC.

|

Do you practice source-level segregation of solid waste generated in your house |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

No |

55 |

15.7 |

|

Yes |

295 |

84.3 |

|

Total |

350 |

100.0 |

Through the quantitative survey conducted, it was found that 84.29% of the respondents perform source-level segregation of household MSW, which is indeed a good sign as far as the community involvement in MSWM is concerned. But the efficiency of management of MSW generated in the household-level needs to be analyzed further, which provides scope for the next level of the study.

A ‘former health inspector’ of TMC also pointed out the benefits of involving the community in TMC’s MSWM through a decentralized approach,

The biggest factor for our success is the attitudinal change that occurred among the people, as a result of the participatory approach facilitated by Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation. According to the latest national green tribunal report, about 45% of the city is performing home composting and according to our reports, above 60% of the city is performing source level or community level composting…”

Thus TMC, which had no alternative mechanism for MSWM in 2012, when its centralized MSW treatment plant was shut down, has taken a major shift to a municipal body treating a major proportion of its food waste through source-level composting. This shift was made possible through the successful involvement of the community.

Efforts for Pooling Community Towards MSWM in TMC

Pooling community participation to the decentralized MSWM approach in TMC was not an easy process. In the initial phase of decentralization in TMC, the community participation was considerably less, worse still, resistance from the community was enormous. It took much effort through strategic awareness campaigns and other programs. A former ‘Mayor of TMC’ recollects,

I would say public awareness and participation are very important as far as any municipal solid waste management approach is concerned. At the beginning of TMC’s decentralization process, there was huge resistance from the city households, as they would need to take up the responsibility of solid waste management equally as TMC. This practice was not adopted till then. But gradually through systematic awareness campaigns, we successfully gained citizen consent and participation to go forward with our mission of a “zero waste city”

The quantitative survey conducted also proved that the awareness campaigns taken up by TMC for promoting decentralized MSWM are making fruitful results.

Table 6: Citizen’s Opinion on Decentralized MSWM Awareness Campaigns of TMC.

|

Do you agree that Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation is successful in its awareness campaigns for promoting decentralized municipal solid waste management |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Agree |

149 |

42.6 |

|

Disagree |

11 |

3.1 |

|

No Opinion |

34 |

9.7 |

|

Strongly Agree |

148 |

42.3 |

|

Strongly Disagree |

8 |

2.3 |

|

Total |

350 |

100.0 |

From the analysis of the quantitative data, it can be understood that above 80% of the respondents either strongly agree (42.29%) or agree (42.57) regarding the success of the awareness campaigns conducted by TMC for the promotion of decentralized MSWM.

Similarly, studies have also reported that public awareness is one of the most important factors, facilitating the success of an MSWM program. It is argued that the local governments need to take the responsibility of generating public awareness in waste segregation through conducting variety of participatory activities, pointing out the economic and environmental benefits of the same. Along with public awareness, public participation, strict laws and policies in the local government and higher government level, and scientific solutions are needed for a viable solid waste management program19.

The ‘founder of an MSWM service provider under TMC’ briefed on the level of community participation for decentralized MSWM in TMC from his experiences as a service provider,

(…) Initially we started our service in the Sasthamangalam ward. During that time, about 60% of the households were responding very well, but about 20-25% of the people needed a push to fall in line with source level waste management. Initially, they weren’t ready to accept any change, but later they came in line seeing the positive results generated among their neighbors. However, the rest of about 15% were reluctant to any change in the system, they are keeping on raising their voice against all the novel initiatives in this field, trying to derail our activities.In the initial wave of decentralization itself, we’ve reached up to 700 households, and then to reach 1,500 houses, we were forced to work to a huge extent due to the adverse effect of these 15% households’ influence.

Thus, according to him, about 85% of the households can be brought together for participatory MSWM, but still, there could be about 15% of households who refuse to take responsibility to be part of MSWM. The reason for that could be many, including politics and prevailing NIMBY syndrome.

A Brief Overview on Institutional MSWM of TMC;

Institutional MSWM is considered to be the generator’s own responsibility in TMC. MSW being generated from establishments such as hotels, restaurants, auditoriums and other bulk generators including flats and gated communities will not be managed under the direct assistance of TMC. But the flats and gated communities would receive 50% subsidy for setting up source-level organic waste management facilities.20

According to an ‘MSWM Consultant’, TMC has allotted service providers for handling institutional waste and there also TMC plays a facilitator role;

Taking the case of institutions, the opportunities for source-level waste management is limited. So TMC has assigned service providers for institutions; different service providers would handle different kinds of waste. TMC makes sure that the service providers are working according to the standard protocol of TMC and whether they are efficiently managing the waste collected. Mainly, food wastes from the institutions are being taken to the piggeries as they need huge amount of waste as pig feed…”

TMC has adopted a semi-centralized model for managing institutional waste. An ‘acclaimed solid waste management expert and consultant’, during an in-depth interview, explained it as an overflow waste management mechanism practiced in TMC. He said that,

We have a definite plan for overflow waste management - houses to community aerobic bins, and sectorial waste management - households to institutional. Also recycling of waste is mostly done in centralized facilities. Thus, it is a mix of appropriate technologies and methods.

Households predominantly follow a source-level waste management model. When it comes to institutions, as the waste quantity is huge, options for centralization is also brought in. In both the approaches, source level segregation is adopted for efficient management. Further, in all categories, that is, among households and among institutions, recycling is centralized, but community participation also occurs in the form of source level segregation.

NGOs as Stakeholders in TMC’s MSWM

When TMC was following a centralized approach in MSWM, the participation of NGOs and other voluntary organizations was very limited. They were not included in any of the major functions of TMC as major stakeholders. As the centralized MSWM approach followed by TMC was a non-participatory movement, there were no specified roles for extended stakeholders, other than the plant operators and waste collectors. But now, NGOs play a major role in TMCs’ decentralized MSWM approach, from the role of consultants to service providers and to educators, many NGOs are associated with TMC.

According to the ‘MSWM consultant’, NGOs’ are playing a vital role in the implementation of decentralized MSWM initiatives. He stated that,

NGOs are now acting as the grass-root driving force of TMC in carrying out MSWM related activities. NGOs in the capacity of service providers are engaged in the household MSWM activities and up to an extent, in institutional level MSWM. In the institutional level, MSWM private companies are also entrusted with certain responsibilities, as the waste generation will be complex and difficult to be handled by small NGOs

Studies have suggested that, for devising integrated management and safe disposal system for MSWM, NGOs and community-based organizations (CBOs) need to be integrated as stakeholders in this sector21. Technical Experts and former bureaucrats who have extensively worked in this area also support the public-private partnership (PPP) Model in MSWM by including NGOs. According to the ‘former executive director of Suchitwa Mission, Government of Kerala’,

I support the adoption of PPP model in MSWM by including NGOs. But there should be clarity in the agreement and the NGOs need to be strictly monitored. This process is not so easy. But you can see now in TMC that, PPP has brought in some service providers and thereby more men and women are getting jobs as well.

A ‘former director- operations, Suchitwa Mission, Government of Kerala’, strongly supported NGO involvement as the grass-root level service providers, envisioned PPP model in MSWM enterprise. According to him,

PPP in MSWM is essential, as all the responsibility can’t be given to the hands of local self-government department, NGOs having core competencies in the field can be included and can work through joint collaborations. The local self-government department can be a core manager in managing some waste and facilitator in case of some other waste.

The ‘founder of an MSWM service provider to TMC’ also supported the idea of PPP model and opined that it would bring in more jobs, that too equally for male and females. According to him,

We have employed a totalof five personnel; four females as green technicians and one male as supervisor. Two male green technicians were also employed; recently they left the job due to some personal reasons, we’ll find replacements for them as soon as possible. Our team is doing a fantastic job and they are given decent salaries. As they need to work only till noon, enough free time is also there for engaging in any other kind of extra income generation activities.

‘Former health inspector of TMC’ said that NGOs and other Voluntary Organizations are actively engaged in the MSWM extended support activities. He said,

We’ve given space for several NGOs’ and voluntary agencies. Further, we have included their suggestions in our municipal solid waste management plan as well. Now they are actively engaged in planning and conducting awareness campaigns along with us.

Many NGOs and Voluntary organizations also support the functioning of TMC’s flagship initiative for environment education; the ‘green army’ through mentoring.20

Contingency Staffsas Stakeholders in TMC’s MSWM

Contingency staffsin TMC played a major role in MSWM in all phases of the Vilappilsalacentralized MSW treatment plant period, especially in the pre, and operational phases. The health department of TMC was in charge of all the MSWM related activities in its jurisdiction. Even before TMC was formed, that is in 1900s itself, ‘Travancore’(the then state which included the TMC area) had a health officer, sanitary inspector and 228 scavengers for 7,427 houses. Further developments in the staffing pattern came after the formation and further expansion of TMC. Until the establishment of the Vilappilsalacentralized MSW treatment plant, the main responsibility of the contingency staffs, known as scavengers, were street sweeping, collection of waste and transportation of waste to multiple dumpsites within the city. Till the period of manual scavenging prohibition, they performed such work as well22, 23, 24.

The role of contingency staffs changed slightly when the Vilappilsalacentralized MSW treatment plant was established. Instead of taking MSW to the dump spots within the city, they were loading the MSW from multiple points into the waste trucks, which was then ferried to Vilappilsala. According to a ‘contingency staff of TMC,

When Vilappilsalaplant started functioning, my main duty was to collect waste from shops and deposit in heavy trucks. After the closure of Vilappilsala, I used to collect waste from certain points. Organic waste was made to compost and inorganic waste was mostly left unattended. But the process did not go very well as the waste which I used to collect was not properly segregated.

Contingency staffs had to work in very unhealthy conditions and they received little respect from society, as their work was regarded as low-graded and thus despicable. Studies have also reported that the conventional forms of collection of MSW and depositing in depots or such collecting points through manual loading caused serious health issues to the workers. This was very time-consuming and resulted in loss of labor productivity25.

However, matters took a turn when TMC adopted a decentralization approach in MSWM. According to the ‘former health inspector’,

Since the adoption of decentralization in municipal solid waste management, the contingency staffsalso got a facelift. We are now considering them as green technicians and they are no longer engaged in mere collection of solid waste. They turned out to be facilitators in solid waste management and perform varied duties such as Management of aerobic bin units, dry waste collection bins, material recovery facilities and resource recovery center. They also perform anti-mosquito drives, street sweeping and often include collection of waste littering the roadsides.

When the decentralization of MSWM was adopted in TMC, a major shift took place in the role of contingency staff, which was limited to the collection and transfer of waste, but now they are the facilitators of TMC’s MSWM. But still, they are officially designated as ‘contingency staffs, which needs a revision that would make them an integral and important part of the whole MSWM system.

Considering the health department of TMC as a whole, TMC is divided into 25 Health circles across 4 zones and 100 wards. Officials of the health department are headed by the secretary of TMC and the health officer. A qualified doctor observes the daily activities of all four zones. Further, health supervisors control each zone and, health inspectors and junior health inspectors coordinate the activities in each circle as well as ward respectively20.

Apart from the staff pattern of MSWM related activities, TMC has constituted a health standing committee headed by a chairman and other members. All of them are politically elected ward councilors to oversee the functions of MSWM and other health-related interventions.

Scrap Workers as Stakeholders in TMC’s MSWM

Considering the Indian MSWM scenario, scrap workers (rag-pickers) play a major role in handling recyclable items, but their role is given very limited recognition. It is mentioned in a study report of ‘chintan’, an NGO based in New Delhi that about 14% of the annual municipal bodies’ budget is being saved by the activities of scrap workers. Scrap workers’ activity also estimates a reduced load of up to 20% on transportation and landfill.17, 26

The scenario is almost similar in the case of TMC as well. Scrap workers play a vital role in MSWM, but they are not being recognized for their work. The extent of work which a normal scrap worker does in his life time could be understood from the words of a senior scrap worker from Tamilnadu, settled in TMC for about 41 years,

Earlier I used to cover at least 25 houses by foot per day and I used to take all sorts of recyclable waste such as plastic, metal, steel and e-waste. I used to hand over the scrap collected to the scrap dealers and from there they again do the segregation. From the scrap dealers, the segregated recyclable waste will be taken to Chennai, Coimbatore and other locations for recycling. But now, as I got some space in my rented house, I collect and bring the scrap here, and re-segregate it and directly handover to the agent, so I get more money in return.

When I started my work, I used to get only 200-250 rupees per day, during that time there were not much demand for these items. But now I get at least INR 500 per day. But extensive walking caused damages to my ligament and now I’m not able to go for collection by foot; instead I hire an auto-rickshaw for the purpose which causes an extra economic burden for me. Also, I’m not going to many houses as I did during my early years of work. During my younger ages, I used to cover the entire southern part of Thiruvananthapuram city and now I cover only few wards around Kudappanakunnu. As of now, I’m just doing this job to generate some extra income; my children are sending me sufficient amount of money which is more than enough for me and wife to survive and they are urging me to stop the work and get some rest. But, I can’t stop it as I’m so much enjoying my job (laughs).

For the scrap worker, he looked after his family, gave good education to the children and provides all the necessary support for his family through collecting the inorganic waste generated in TMC. At the same time, he has helped TMC directly from re-rooting a proportion of inorganic waste from entering its waste stream and then to the dumpsites. There are many scrap workers working in TMC limit, who play a major role in keeping the surroundings clean and facilitating in smoother MSWM.

However, the question is whether the scrap workers, who are important stakeholders in TMC’s MSWM are being treated fairly for their work and commitment. From the words of the scrap worker, it can be understood that they are neither integrated formally into TMC’s MSWM initiatives nor any kind of assistance in the form of medical insurance or any other welfare activities are being rendered to them.

During the rather exhaustive interview, the scrap worker also indicated a major concern, Now the people engaging in this field are comparatively lesser and in TMC it is very less when compared to previous scenarios.FGD 1 conducted in the Department of Sociology, University of Kerala gave an insight of how scrap workers play a pivotal role in institutional waste handling. A participant of the FGD said that,

Here, once in a while the University authorities contract some scrap dealers to take away the e-waste from all the departments. Also the plastic bottles being deposited in various points across the campus are also given to scrap workers at some point of time each year.

Like in the University of Kerala, across the houses and institutions in TMC, scrap workers are playing a major role in the movement of recyclable inorganic waste. Albeit, the decrease in number of scrap workers could directly impact the inorganic waste management of TMC, as they are handling a major share or recyclable materials. As TMC is following a decentralized model of MSWM, inclusion of grass-root workforce such as scrap workers into their system is of much importance and it is high time to do so.

Political Leaders as Stakeholders in TMC’s MSWM

Political leadership or decision-makers are able to highly influence the MSWM process of a municipal body, positively or negatively. Former Health Inspector said during the indepth interview,

Only a council with good leadership can take Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation’s decentralized MSWM initiative forward. From the initiation of decentralization in MSWM itself, we are getting enough support and encouragement from the TMC’s leadership. The entire three Mayors’ during this tenure, from the initiation of decentralized MSWM were active in creating awareness among the people regarding the importance of efficient MSWM system. Also, they were active in taking decisions for the adoption of sustainable technologies, promotion of waste reduction strategies such as green protocol and recycling and in conduction of frequent evaluations of the strategies adopted.

Studies have also revealed that the municipal leader’s awareness regarding the impact of the waste management systems and knowledge on new technologies and good waste management practices helps in setting up appropriate waste segregation programs. Further, the interest of local leaders in solid waste management helps in the allocation of necessary funds for equipment and infrastructure, covering of waste at the disposal site, promotion of more efficient collection system, better infrastructure and low-cost recycling technologies.27

Support from the political leaders of opposition parties is also essential for the effective implementation of an MSWM strategy. According to a ruling party ward councilor,

At the grass-root level, I’m getting political support from all the political parties. It can be considered as an important factor, which helped me make my ward a clean ward. They only see rivalry during elections, that too in a very professional manner. This could be a subjective case; maybe in other words, the situation would be different.

Conversely, contrasting views regarding the unfair distribution of services were provided in the wards where opposition council members represent. According to a ‘ward councilor’ who belongs to the opposition party of TMC,

The services rendered are concentrated only in certain wards. Most of the activities, including setting up of material recovery facilities, community aerobic bins and distribution of bio-composters are being concentrated largely on ruling party wards.

A similar statement was given by another ward councilor who belongs to the opposition party,

My ward is situated very next to the former Mayor’s ward. You yourself can see that his ward has got all the necessary infrastructures for solid waste management from portable aerobic bins to material recovery facility and even a swap shop. But, the very next ward that I represent hasn’t got any such facility from TMC; not even the supply of household composting devices. This has led to an increase in the dumping of waste in my ward. I have taken up this issue of waste dumping in the council, but the mayor just squashed my statements by saying that I’m just politicizing the solid waste management issue. I’m neither aware about the discussions of the technical committee formed for the purpose of facilitating solid waste management in TMC nor have I been invited to be a part of the committee.

The complaints raised by the two councilors belonging to the opposition party need to be addressed with high priority, as TMC can only be regarded as having a sustainable MSWM system if the services are equally distributed among all the 100 wards irrespective of the particular ward’s political alignment.

The issue of politicization of the MSWM can be seen in other countries as well. For instance, such unequal distribution of services was reported in Malaysia after its general elections in 2008. The states with the same political coalition as the federal Government received more effective MSWM services based on the solid waste management act of 2007 than that of the states with different political coalition.28

Notwithstanding, another opposition party ward councilor had a different experience to share,

I received severe objections from my own party members while implementing innovative MSWM initiatives in line with TMC’s decentralized approach in the Poojappura ward. Conversely, the Mayor and other key leaders of the ruling party stood with me and I have succeeded in establishing a fair number of community aerobic bin facilities, a material recovery facility and have distributed home composting devices to many households. I see the objections from my party members as just a mere political ego existing in their minds. They all believe that if I did something good for my ward, the credit shall go to the TMC leadership. But I’m completely professional when it comes to my duty. I don’t care what my party members or any other party people think of regarding my work. I’m here to serve my people and I’ll do it as a committed ward councilor.

On comparing the statements of the three opposition councilors, it is clear that, if only the local level political representatives engage in issues like solid waste management beyond sectarian political motives, they could act more professionally and stay committed towards their responsibility towards the public, which could address such issues at the grassroots. Therefore, it can be surmised that the attitude and commitment of the local political leadership plays a major role in the effective implementation of MSWM strategies. The quantitative survey result shows that the interventions of the ward councilors of TMC in MSWM related activities are not satisfactory.

Table 7: Citizen’s Opinion on Ward Councilors MSWM Interventions on MSWM Related Activities.

|

Are you satisfied with your ward councilor’s interventions in municipal solid waste management related activities |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Dissatisfied |

76 |

21.7 |

|

Highly dissatisfied |

35 |

10.0 |

|

Highly satisfied |

31 |

8.9 |

|

No Opinion |

86 |

24.6 |

|

Satisfied |

122 |

34.9 |

|

Total |

350 |

100.0 |

From the quantitative data, it can be surmised that more than 50% of the respondents, either have no opinion (24.57%) or are dissatisfied (21.71%) or highly dissatisfied (10%) with the intervention of the Ward Councilor in MSWM related activities. Still, 34.86% of the respondents are satisfied with their ward Councilor’s intervention in MSWM related activities, which also gives some amount of scope for improvement in this regard.

Discussion

Undoubtedly, for a sustainable MSWM,multi-stakeholders participation is very important. The discussion hitherto reveals the fact that the centralized MSWM is not adequately stakeholder-oriented. As a matter of fact, it was found that when the decentralized method of MSWM was initiated in TMC, the level of stakeholders’ participation increased substantially. Studies have corroborated the merits of sustainability in decentralized MSWM when compared to centralized MSWM due to effective participation of local stakeholders in decision making and execution.4, 29

In this study, the role of community, NGOs, ground-level workers (contingency staffs as designated in TMC), scrap workers and political leaders was discussed from a stakeholders perspective during the centralization and decentralization phase of MSWM in TMC. This discussion has helped to review the role and influence of community participation and stakeholders’ involvement for sustainable stakeholders-oriented MSWM.

There was only limited or no community participation while TMC was following a centralized MSWM. The residents of TMC were only waste generators and there was little participation in any kind of waste management or waste reduction activities. The absence of community participation, in fact, contributed severely to its failure. In the decentralization phase of TMC’s MSWM, a certain level of community participation in waste management and waste reduction initiatives can be observed. Studies have also shown that a decentralized MSWM system has more scope for community participation, as it provides more avenues for the members of the community to engage in waste management, which in turn also changed the mindset not only towards MSWM but also on waste generation and waste reduction30.

As in the case of community participation, the involvement of NGOs was very limited during the period of centralized MSWM in TMC. However, the situation has changed radically, as many NGOs are working as service providers and consultants to the TMC, promoting sustainable MSWM. NGOs functioning as service providers to the TMC have created many livelihood opportunities as well. Studies also support engaging NGOs and community based organizations in MSWM operations, as it could reduce the huge expenditure burden of local bodies and would facilitate the execution of economically feasible models29.

As discussed earlier, unlike the community and NGOs, contingency staffs have played a crucial role, both in the centralization as well as decentralization period of MSWM. Nevertheless, they had a low profile and dehumanizing working environment when the Vilappilsalacentralized MSW treatment plant was active. Their main activity was a collection of MSW and loading it into huge trucks, which were sent to Vilappilsala for further management. But in the decentralization phase of MSWM, both the profile and the working conditions of the contingency staff of TMC have changed for the better. Now they are considered facilitators of MSWM and they do not need to engage in conventional MSWM activities.

The scrap workers do play a vital role in recyclable waste management in TMC, but they remain informal stakeholders, both in the centralized and decentralized MSWM process. Studies suggest that the role of scrap workers needs to be recognized and they must be accommodated into the formal system in order to upgrade and boost their morale17. This could help in more employment generation, revenue and ultimately reduce the load on transportation and landfill.

Political leaders or their influence on MSWM varies considerably in centralized and decentralized MSWM. As far as centralized MSWM is concerned, waste management plants tend to be located in the areas of the socio-politically weaker sections, as evidenced in the Vilappilsalacentralized MSW treatment plant. It is said that along with socio-economic dimensions, political lineation of an area is also a consideration for setting up a landfill site29, 31. In the case of decentralized MSWM, since the power is distributed to the grass root level, local bodies can exercise more autonomy in deciding the MSWM strategies for implementation. The efficiency and commitment of the ward councilor is important factor that could contribute to the sustainability and effectiveness of MSWM in a given locality. Unfortunately, the performance of MSWM related activities majority of TMC’s Ward Councilorsis not satisfactory.

Conclusion

From TMC’s experience during its centralization phase, the only stakeholders were its own contingency staff, a few kudumbasree members (self-help group) and a private company operating the MSW treatment plant. Even the residents of TMC did not have much role or responsibility other than just handing over the daily waste generated in their premises.

Multi-stakeholders participation has increased substantially, as TMC adopted the decentralized approachin MSWM, which directly contributed to the effectiveness and sustainability of the cause. However, scrap workers’ efforts in the field are yet to be properly recognized or appreciated in TMC. This situation needs to be addressed, as scrap workers are major catalysts in the inorganic waste management system of TMC. Moreover, the ground-level political system of the TMC needs to exhibit more commitment in MSWM related activities as in the case of decentralization. The Ward Councilors have a great role in bringing grass-root changes.

Thus for cities like TMC, where population is booming and MSW generation is increasing, multiple stakeholders’ participation is crucial for MSWM to be sustainable. Moreover, there is an urgent need for carrying out waste reduction initiatives. For such a coordinated effort to mature, MSWM needs to be stakeholder-oriented and preferably follow an approach of decentralization.

Acknowledgments

The authors whole heartedly thank Hon’ble Mayor, Deputy Mayor, Health Standing Committee Chairman, Ward Councilors and Health and Sanitation Department Staff of Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation for extending their support for the successful completion of the study. The authors also extend our gratitude to Adv. V.K Prasanth, Member Legislative Assembly, Kerala, Mr. Anoop Roy, Former Health Inspector, Thiruvananthapuram Municipal Corporation, Mr. Sugathan S., Executive Director, Green Village, Ms. Babitha P.S., Founding Mentor, Green Army and all the respondents of the study for their wholehearted support and cooperation.The authors is also profoundly grateful to Suchitwa Mission, Government of Keralafor the guidance during the data analysis.

Funding Source

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Visvanathan C, Trankler J. Municipal Solid Waste Management in Asia: A Comparative Analysis. Paper presented at: Workshop on Sustainable Landfill Management.; December 3-5, 2003;Chennai.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242220878_Municipal_Solid_Waste_Management_in_Asia_A_Comparative_Analysis.Accessed date: December 20, 2020

- Joseph K. Stakeholder participation for sustainable waste management. Habitat International. 2006; 30(4):863-871. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.09.009.

CrossRef - Van de Klundert A, Anschutz J. Tools for Decision-Makers : Experiences from the Urban Waste Expertise Programme (1995-2001). Netherlands: WASTE; 2001.

- GEAG. Decentralized Solid Waste Management through Community Participation. Uttar Pradesh: ACCRN; 2012.20. https://geagindia.org/publications/decentralised-solid-waste-management-through-community-participation-pilot-programme.Accessed December 25, 2020.

- Rothenberger S, Zurbrügg C, Enayetullah I, Sinha A. Decentralised Composting for Cities of Low- and Middle- Income Countries -- A Users’ Manual.Dhaka. Waste Concern; 2006.

- Sasikumar K, Krishna S. Solid Waste Management. Delhi: PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.; 2009.

- Baud I, Schenk H. Solid Waste Management: Modes, Assessments, Appraisals, and Linkages in Bangalore. Delhi: Manohar; 1994.

- Furedy C. Garbage: Exploring non-conventional options in Asian cities. Ekistics. 1993;60(358/359):92-98.

- Wilderer P A, Schreff D. Decentralized and centralized wastewater management: a challenge for technology developers. Water Sci Technol. 2000;41(1):1-8. doi:10.2166/wst.2000.0001.

CrossRef - Brulle R J, Pellow D N. Environmental Justice: Human Health and Environmental Inequalities. Annual Review of Public Health. 2006;27(1):103-124. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102124.

CrossRef - Lober DJ. Why Protest? Policy Studies Journal. 1995;23(3):499-518. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.1995.tb00526.x.

CrossRef - Moore S. Waste Practices and Politics: The Case of Oaxaca, Mexico. In: Carruthers D. Environmental Justice in Latin America: Problems, Promise, and Practice. Vol 21. 7th ed. Massachusetts: The MIT Press; 2008.

CrossRef - Harikumar L. Decentralization and Development In Urban Local Government A Study of Thiruvananthapuram Corporation 1995-2005. [PhD Thesis]. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: University of Kerala; 2013.

- AG Report. Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India : For the Year Ended 31 March 2011. Controller and Auditor General of India; 2011.85.

- Eriksson O, Bisaillon M. Multiple system modeling of waste management. Waste Management. 2011;31(12):2620-2630. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2011.07.007.

CrossRef - Sinthumule NI, Mkumbuzi SH. Participation in Community-Based Solid Waste Management in Nkulumane Suburb, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. Resources. 2019; 8(30):1-16. doi:10.3390/RESOURCES8010030.

CrossRef - Joshi R, Ahmed S. Status and challenges of municipal solid waste management in India: A review. Ng CA, ed. Cogent Environmental Science. 2016;2 (1):1-18. doi:10.1080/23311843.2016.1139434.

CrossRef - Singh R. Exploring the potential of decentralised solid waste management in New Delhi. Published online April 30, 2015:19. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.5118.6088.

- Awasthi M, Zhao J, Soundari P, Kumar S. Sustainable Management of Solid Waste. In: Taherzadeh M, Bolton K, Wong J, Pandey A. Sustainable Resource Recovery and Zero Waste Approaches. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019:79-99. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64200-4.00006-2. Accessed date: March 23, 2020.

CrossRef - Ramachandran K. Greening Kerala: The Zero Waste Way.Thiruvananthapuram-India: Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives; 2019:8. https://zerowasteworld.org/zwsolutionsasia/. Published date: October 17, 2019. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Ahsan A, Alamgir M, Imteaz M, Daud NN, Islam R. Role of NGOs and CBOs in Waste Management. Iranian journal of public health. 2012;41(6):27-38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23113191/. Published date: June 30, 2012. Accessed March 21, 2021.

- Aiya V. The Travancore State Manual. Vol 12. Thiruvananthapuram: The Government of Travancore; 1906.

- Velupillai TK. Travancore State Manual. Vol. 14. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore; 1940.

- Ganesan P. Landfill sites, solid waste management and people’s resistance: a study of two municipal corporations in Kerala. International Journal of Environmental Studies. 2017;74(6):958-978. doi:10.1080/00207233.2017.1374076.

CrossRef - Asnani PU, Zurbrugg C. Improving Municipal Solid Waste Management in India: A Sourcebook for Policymakers and Practitioners. Washington D.C. World Bank Publications; 2007.

- Pappu A, Saxena M, Asolekar SR. Solid wastes generation in India and their recycling potential in building materials. Building and Environment. 2007;42(6):2311-2320. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.04.015.

CrossRef - Guerrero LA, Maas G, Hogland W. Solid waste management challenges for cities in developing countries. Waste Management. 2013;33(1):220-232. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2012.09.008.

CrossRef - Mukhtar EM, Williams ID, Shaw PJ. Visibility of fundamental solid waste management factors in developing countries. Detritus. 2018;1(1):162. doi:10.26403/detritus/2018.16.

- Massoud MA, Mokbel M, Alawieh S, Yassin N. Towards improved governance for sustainable solid waste management in Lebanon: Centralised vs decentralised approaches: Waste Management & Research. 2019; 37(7):686-697.

CrossRef - Singh S, ed. Decentralized Solid Waste Management in India: A Perspective On Technological Options. In: Cities : The 21st Century India. Delhi: Bookwell; 2015:290-304.

- Ahmad SZ, Ahamad MSS, Yusoff MS. A Comprehensive Review of Environmental, Physical and Socio-Economic (EPSE) Criteria for Spatial Site Selection of Landfills in Malaysia. Applied Mechanics and Materials. 2015;802: 412-418. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.802.412.

CrossRef