Women at the Forefront of Environmental Conservation

1

Department of Botany,

Sri Aurobindo College, University of Delhi,

New Delhi,

India

2

Department of Botany,

Dyal Singh College, University of Delhi,

New Delhi,

India

3

Department of Electronics,

Sri Aurobindo College, University of Delhi,

New Delhi,

India

4

Department of Chemistry,

Sri Aurobindo College, University of Delhi,

New Delhi,

India

5

Shaheed Rajguru College,

University of Delhi,

New Delhi,

India

6

Department of Botany,

Swami Shraddhanand College, University of Delhi,

New Delhi,

India

Corresponding author Email: isha@ss.du.ac.in

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.18.2.22

Copy the following to cite this article:

Mathur R, Katyal R, Bhalla V, Tanwar L, Mago P, Gunwal I. Women at the Forefront of Environmental Conservation. Curr World Environ 2023;18(2). DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.18.2.22

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Mathur R, Katyal R, Bhalla V, Tanwar L, Mago P, Gunwal I. Women at the Forefront of Environmental Conservation. Curr World Environ 2023;18(2).

Download article (pdf)

Citation Manager

Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 2023-04-04 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 2023-06-19 |

| Reviewed by: |

Devagi Sivaraj

Devagi Sivaraj

|

| Second Review by: |

Shaibur Rahman Molla

Shaibur Rahman Molla

|

| Final Approval by: | Dr. Hiren B. Soni |

Introduction

In developing countries, women are predominantly dependent on nature for survival. Women's innate sensitivity to the environment, natural skills for resource management, and structured ecological consciousness make them competent conservationists. Women in the developing world are usually in charge of managing and protecting their families' resources. They spend most of their time maintaining forests, wetlands, and farms and obtaining and storing food, firewood, water, and livestock feed. They provide food for the majority of people, especially in rural areas. About 60 to 80 percent of food is produced by women alone in developing nations1. Moreover, women are devoted to children and the elderly making them indispensable to their communities. Communities also benefit from their traditional knowledge of biodiversity in many ways for food, medicine, ??and healthcare2.When the availability of these resources reduces, due to extreme weather conditions like famine, unpredictable or heavy rainfall, the lives of women and their families get affected. Women are more likely to be impacted by natural disasters than men3. Women account for more than half of the global population yet they own only 2 percent of land globally1. Women do not have direct control over land due to inheritance laws and local customs that make it hard for them to own or rent land, get loans, or purchase insurance to safeguard their assets. A key barrier to women's empowerment and poverty reduction is the lack of fair land rights4

Over the past few decades, environmental deterioration has become a "matter of concern". The environmental concerns are mainly due to human activities. Industrialization, urbanization, and a growing population pose a serious threat to the environment. Lack of awareness and sensitivity towards the environment has led to the degradation of ecosystems, natural resources, loss of biodiversity, and climate change. Women initiated various forms of movements, protests, awareness campaigns, and community involvement programs across the globe in this connection. Environmental movements are social or ethical movements that aim to conserve or enhance the quality of the environment, protect biodiversity, promote natural resource sustainability, and advocate for policy reforms to safeguard the environment. The movements are concerned with ecology, health, and human rights.

Women have faced numerous challenges, but through their skill and determination, they have persevered in striving towards the betterment of the environment. Though often overlooked, women have played a pivotal role in every environmental movement. The contribution of women environment activists needs to be acknowledged to attain long-term growth and prosperity for a promising future. The roles and responsibilities of women in environmental movements seem very different in different parts of the world. In industrialized nations, women's concerns are often linked to issues such as pollution5 and the urban environment, whereas in underdeveloped countries they are linked to rural livelihood challenges. Environment protection movements in India like the Chipko movement, the Jungle Bachao Andolan, the Silent Valley movement, the Bishnoi movement, the Narmada Bachao Andolan, etc., all highlight the relevance of ideas and opinions of women in designing futuristic strategies6. The Millennium Development Goals necessitate environmental sustainability and gender equality since they strongly emphasize people's welfare. Without involving women in the planning and policy-making, it is impossible to achieve the goals of conservation of natural resources and the environment7.

Women are more concerned and committed to environmental conservation on a global scale8. In the early 1970s, Ester Boserup attempted to attract attention to the link between women, the environment, and economic growth9. Women were at the forefront of the Chipko movement in India in the 1970s10. They succeeded in their protest to prevent the trees from being cut down by hugging them. Women were also able to preserve and protect natural water in its pristine form by preventing businesses from monopolizing natural water bodies. They were instrumental in founding several well-known groups, such as the Green Belt Movement, a reforestation and restoration project launched in Kenya on Earth Day in 197711.

By the 1980s, administrative officials and politicians gained a greater understanding of the connection between environmental concerns and gender inequalities. The first changes in how natural resources and the environment are to be protected emerged with the unique role of women in mind. The vital role of women participation and important links between women and the environment have been recognized in sustainable development accords12.

Two significant accords on biological diversity and desertification generated from the Earth Summit (1992) of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), have guided gender-sensitive environmental action. The UNCED manifesto has a segment on gender issues that highlights women's role as sustainable consumers in developed countries 12. According to a 2007 Swedish government survey, women in the developed countries make the majority of "green" household and travel decisions and have a smaller carbon footprint13.

Women all over the world strive to combat climate change by adopting sustainable consumer choices and enhancing resource access, control, and conservation. Policy and implementation initiatives for the benefit of the present and future are dependent on their input. WEDO (Women's Environment and Development Organization) was founded with the specific goal of influencing the 1992 UNCED through women's worldwide participation and inclusion. The organization is dedicated to promoting gender equality in decision-making for the benefit of economic and social justice. As an outcome of WEDO's efforts, the first-ever gender-specific text was incorporated into the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations, UNFCCC 2019. According to these international agreements, all women must have a say in the policy making decisions about their environment. Women have made significant contributions to the success of the environmental movements by serving as leaders, thinkers, experts, strategists, educators, and role models.

Throughout the world, researchers have been making a concerted effort to demonstrate the connection between gender equality and a healthy ecosystem and how Investment in long-term economic, human, and environmental capital is essential for achieving sustainable development.

Since women's caregiving obligations and economic activities are largely dependent on natural resources, they have a key role in conservation and restoration initiatives. As an example, in nearly 75% of homes without clean drinking water, women play a pivotal role in sourcing the commodity13. There is also a relation between environmental degradation and reluctance to recognize women's rights. Countries with more women in their parliaments are more likely to protect their land and sign environmental treaties6. According to Forbes Magazine, the commonality between nations with the best response to the Covid 19 pandemic was that they had women leaders!14

Ecological movements arising from conflicts over natural resources and people's survival rights are spreading in regions of the Indian subcontinent. Most natural resources are already being over exploited to provide for the majority of people's most basic requirements. As the predatory exploitation of natural resources to support development has grown in scope and severity, so has the intensity and range of ecological movements in independent India.

Environmental movements in India have gained momentum over the past few decades, bringing to light a wide range of pressing concerns. Leading environment expert Harsh Sethi divides India's environmental conflicts into five groups15:

- Forest-based policy: forest resource utilization,

- Land use policy: industrialization, indiscriminate dumping of chemicals, land, and water degradation; resulting in loss of agriculture,

- Against large dams, which cause environmental degradation, including forest destruction, and the forced relocation of tribal and non-tribal residents residing upstream of the river,

- Against industrial pollution and,

- Against the overuse of marine resources.

In India, those who support environmentalists and environmental causes are the marginalized poor, the evicted, the Dalits, the women, the indigenous people, and the small or landless farmers. Women are the protectors of biodiversity since they do the majority of the work on the farm, including planting, weeding, and harvesting. Furthermore, women have a strong connection with their surroundings through their daily interactions as collectors of water and fire-woods. The theory of eco-feminism came into existence as a result of the close relationship between women and nature.

Environment conservation movements led by Women in India

Women and the environment are inextricably connected. Women are therefore, paramount to any endeavor to promote sustainable development and environmental protection. Women have historically made significant contributions to conservation movements, exemplifying their fundamental leadership. Following are some of the environmental movements that highlight the role of women in leading ecological revolutions.

The Bishnoi movement

Was a wildlife protection movement, in the early 18th century, wherein as many as 363 members of the Bishnoi community sacrificed their lives in an effort to prevent the king's soldiers from felling the trees so that a palace could be built. The Bishnoi community observes strict laws to defend all components of nature (plants, animals, and the environment). The Bishnoi community steadfastly opposed tree-cutting and persisted in its opposition to deforestation. This movement was responsible for creating the idea of hugging or embracing trees as a kind of protection. The Bishnoi resistance in 1730 served as a foundation for the 1970s Chipko movement, which was a nonviolent uprising by Himalayan people to stop logging. The Bishnoi movement was one of the oldest social movements with an emphasis on environmental protection16,17.

The Community practice 'Thengapalli'

Odisha's indigenous women have been practicing Thengapalli, (thenga means stick and palli means to turn) wherein they have been willingly preserving and protecting their forest area for many years, by patrolling in groups of four to six, each carrying a stick. Thengapalli originated in the early 1970s in the Nayagarh district of Odisha, but it didn't truly take off until the 1990s. Women have been in charge of watching the forests in at least 300 communities in Nayagarh, being responsible for forest conservation in the village of Gunduribadi, and in the rehabilitation of almost 500 acres of forest area18,19,20.

Chipko movement

The movement had spread throughout Uttarakhand in the Himalayas, started in Chamoli district in the year 1974, led by protestors Bachni Devi and Gaura Devi. The protest was in response to the approval by the state government corporation for commercial logging. In an effort to save their forests rural women gathered to hug trees as contractors approached to cut them down. One of the most noticeable characteristics of this movement was the widespread, voluntary participation of women from the village. The Chipko Movement aimed to preserve the ecological equilibrium in the vulnerable Terai or lowland region, where an ecologically balanced relationship with the environment has been historically maintained by the hill people. The Chipko movement had an effect well beyond Himalaya’s Uttarakhand area. The movement influenced similar efforts to preserve forests in other parts of the country21,22.

The Silent Valley movement

Opposed the Kerala government's decision to construct a dam in the Silent Valley Forest for a hydroelectric project (1975-1984). An important figure in this movement was the environmentalist and Malayalam poet Sugatha Kumari. Residents, particularly women, were against the hydroelectric project despite the potential for employment and development in the region. Silent Valley became a national park in 1984 after the project was scrapped in 1980 due to direct intervention by the country's then-prime minister, Indira Gandhi23,24,25.

The Appiko movement was sparked by the Chipko movement, in the 1980s to safeguard the jungle in Uttara Kannada, Karnataka. The movement was led by Panduranga Hegde. A number of industries such as paper mills, and plywood factories, overexploited forest resources, and a chain of hydroelectric dams sprouted which submerged vast forest and agricultural areas. By 1980, all these activities resulted in the shrinking of the forest to about a quarter of its original size. In light of this catastrophe, the Appiko Movement emerged intending to protect and preserve the Western Ghats26. During 1983 and 1990, residents of Karnataka, India, used a technique called "tree hugging" (Appiko) to prevent any further deforestation27. In southern India, the movement helped raise awareness of environmental protection, and many rural women were involved.

Gandhamardan movement: The Gandhamardan hills are widely recognized as an "Ayurveda Paradise" due to the extraordinary variety of medicinal plants, orchids, and other unusual species that can be found there. Furthermore, bauxite is abundant in the hills. The hills, which support the livelihood of the tribals and are crucial for maintaining the ecosystem of the area, have been the venue of one of India's most outspoken individuals battles to protect forests and their way of life. The struggle to defend Gandhamardan Hill began with the Balco (Bharat Aluminum Company) mining operations in the 1980s by the tribal people whose survival was directly impacted by the extraction of bauxite reserves. Balco's operation to extract 213 million tons of bauxite was shut down as a result of a five-year-long, persistent campaign by the locals. It was a big victory for both the local environment and the inhabitants of western Orissa, who were dependent on the forests. The BALCO project posed a threat to desertifying and deforesting the hill slopes where people had been performing their religious practices. It put thousands of independent farmers whose families had farmed the same land for generations in danger of losing their way of life. The Gandhamardan Hills' local communities launched a campaign to protect the area's abundant biodiversity. The tribal people disagreed with the contemporary development idea, which involves displacing locals and enabling mining. The locals have been successful in defending the forests and resources from commercial exploitation28,29.

Jungle Bachao Aandolan was a protest started in 1982 by the tribal people from the Singhbhum district in Bihar, to oppose the decision of the politicians and government officials to replace the Sal trees in the forests with the plantation of commercially profitable teak. The movement to swap out the Sal forests for economically viable teak, became popular as "Greed Game Political Populism". The movement, which was born out of a fight to restore the forest rights of the tribal people, later moved to Orissa and Jharkhand. The tribal people realized that the best way to safeguard their forests was to assert their ownership rights over them. Suryamani Bhagat helped organize resistance and talks with the government, which led to the Forest Rights Act being passed in 200630,31.

Deccan Development Society was established in 1983, with the goal of helping the most vulnerable families in Andhra Pradesh's arid Medak district. The society has 5000 women members, from 75 villages, it envisions a participatory development, with special emphasis on food security, eco-friendly agriculture, and alternative forms of education for everyone. Women's groups, or sanghas, play a significant role in society. Society is making an effort to preserve traditional knowledge of agriculture and health, through a variety of land-related initiatives like The Community Grain Banks, The Community Gene Funds, Permaculture, The Community Green Funds, and The Collective Cultivation. These are efforts to undo the damage done to the environment and the socioeconomic principles of the local population over time in the region32. The society has received many prestigious awards for their initiatives towards sustainable development, and biodiversity conservation practices. Their wisdom and practice of working in harmony with nature, to protect the environment and conserve the rich biodiversity has led them to firmly establish the belief that millet crops have an extraordinary capability to withstand changes in climate and the nutritive significance of these traditional crops. The women organized a country wide campaign as The All-India Millet Sisters (AIMS) to ensure that millets are included in India's Public Distributive Systems as promised by the Food Security Act of 201333.

Navadanya movement was founded in 1984 by environmentalist Vandana Shiva to promote conventional farming practices in India. "Navadanya '' is the largest organic farming movement which means nine crops. It is a nonprofit organization that supports organic farming methods and the preservation of biodiversity. The organization has promoted premium organic food to consumers in addition to helping farmers establish markets. Navdanya's primary objective is to protect seed diversity in the face of biopiracy, and for this they set up 111 community seed banks across 17 Indian states. They are fighting against GMO (Genetically Modified Organisms) seeds and are involved in biodiversity conservation efforts. Most members of the Navadanya Movement are female farmers from all over India34.

Narmada Bachao Andolan is a social movement organized and led by locals, environmentalists, and human rights activists. It was organized to resist the multiple massive dam projects across the Narmada River due to their significant ecological and socio-economic implications. One of the largest dams on the river Narmada is the Sardar Sarovar Dam, providing electricity and water for irrigation to Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh.

Several species of ethnobotanical significance were predicted to become extinct as a result of the area being submerged due to the construction of the dam, according to an environmental impact assessment report on the Narmada Sagar Project conducted by the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. The project was opposed by tribal organizations and villagers who had been uprooted by the reservoir's flooding. To stop the project from destroying local ecosystems and displacing roughly a million people, there were several large demonstrations35.36.

Women at the helm of the environmental protection movement

Amrita Devi is India's first documented female environmental activist. Around 300 years ago, Amrita Devi led a protest in Rajasthan, India, against the felling of trees to make way for a palace for the Maharaja of Jodhpur. The failure of her attempt provoked significant outrage in the community. According to folklore, the king vowed not to ask local communities for wood again. Amrita Devi belonged to the Bishnoi community, which is well-known for its reverence and love of nature37.

Rachel Louise Carson: was a marine scientist and environmentalist from the United States. Her book Silent Spring (1962), and other writings that focus on environmental science, initiated the launch of a nationwide environment movement that faced strong resistance from chemical industries. However, it ultimately resulted in the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the United States and a change in national policy that banned DDT and other pesticides. The book provides evidence of the harm that careless pesticide use has wreaked on the natural environment. She insisted that the chemical business was propagating incorrect information and that the government officials had hastily accepted the industry's advertising claims. President Jimmy Carter presented Carson with the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously38,39.

Parbati Barua is a specialist who has worked on improving human-elephant relations. She is a trainer, teacher, and counselor to elephant handlers and Forest Service officials around the nation because of her reputation as a guru and elephant whisperer. She recently received honors for her efforts to save elephants. The Kolkata International Wildlife and Environment Film Festival has honored her with the lifetime achievement award40.

Gaura Devi, the pioneer of the Chipko (which means "to embrace") movement, advocated for women to hug trees to protect them and prevent them from being cut down. In the Reni village, where she served as the Mahila Mangal Dal's leader, she led 27 women to oppose the lumbermen on the day they were scheduled to cut the trees. The movement was based on the Gandhian philosophy of peaceful resistance, to oppose the destruction of ecological balance. Taking its cue from Gandhi's advocacy of nonviolent resistance, the core of the movement was an effort to peacefully stop the destruction of the planet's delicate ecological harmony. The government's decision in January 1974, to auction 2,500 trees overlooking the Alaknanda River, because the forest property was being given to a manufacturer of sporting goods, served as the impetus for the Chipko Movement, when the women from Uttarakhand's Chamoli village started hugging trees to prevent them from being cut, despite being threatened. They stayed up all night watching the trees until the lumbermen gave up and left. As soon as word of the movement reached nearby villages, more residents joined in. In other parts of Uttarakhand, a similar mode of protest was used, indicating that women were campaigning for the environment10, 41,42,43,44.

Sarala Behn joined Gandhi's nonviolent, socially just cause and supported the struggle against colonialism, imperialism, racial injustice, and gender inequality. She later became a renowned environmentalist and played a significant role in raising awareness of environmental issues in post-independence India. She influenced and led the Chipko movement as an environmental activist by raising awareness of the environmental crisis engulfing the Himalayan region. The Uttarakhand Sarvodaya Mandal was founded by her in 1961 with the primary objectives of organizing women, establishing forest-based small-scale industries, and protecting forest rights. The Mandal and its members labored assiduously to counteract the commercialization of forests. In response to the Stockholm Conference in 1972, she launched the Chipko Movement with a public protest in the Yamuna valley, near the spot where the colonial government had killed activists in the 1930s while they were opposing the commercialization of forests. The Chipko Movement was organized in 1977 to protest the widespread felling of trees for timber and excessive resin extraction from pine cones, Sarla Behn was an integral part of strengthening the movement. She wrote 22 books on issues like environmental protection, gender equality, and conservation. Her works include Reviving Our Dying Planet and A Blueprint for Survival of the Hills45,46.

Professor Wangari Maathai is a political, social, and environmental activist from Kenya. She made history by being the first woman from her continent to receive the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize. She established the GBM (Green Belt Movement) in the year 1977 which is run by the National Council of Women of Kenya. The movement aims to solve the issues of rural Kenyan women regarding the drying up of streams, the dwindling food supplies, and the increasingly longer trek to obtain firewood for fuel and fence. GBM focused on planting trees, protecting the environment, and providing women with equal opportunities and rights. GBM motivated women to plant trees and raise seedlings, to improve the quality of soil, collect and store rainwater, increase food and wood supplies, and also earn some money in exchange for their labor. She was conferred the Right Livelihood Award for her efforts in converting Kenya's ecological concerns into extensive reforestation efforts. She served as an Honorary Councilor for the World Future Council. In addition to being an activist, Maathai was a brilliant thinker who made significant contributions to our understanding of sustainable development, gender concerns, and African cultures and faiths47,48,49,50.

Suryamani Bhagat is a tribal forest activist from the Kothari village of Jharkhand. She collaborated with other women to safeguard forests. She pioneered the Jharkhand-Save the Forest Movement with only 15 tribal women to oppose government officials' plans to plant expensive teak trees that would be useless to the community that relies on the forest29.

Sugathakumari is a poet and environmentalist, who has devoted most of her work to the natural world. Sugatha kumari played a significant role in the Save Silent Valley Movement, one of India's earliest modern-day environmental movements, which began in 1978 and ended when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi canceled a controversial hydroelectric power project in 1983. The contentious project could have destroyed valuable forests in 89.52 square kilometers of land. One of the first activists for environmental protection in contemporary India, she was an important figure in the Save Silent Valley Movement51.

Lois Gibbs is an environmentalist and executive director of The Center for Health, Environment, and Justice. She has been an influential force in leading the environmental movement in the US for many years. The narratives of chemical pollution near Niagara Falls, New York, alarmed her in 1978. She suspected that the peculiar health issues of her children and people living in her neighborhood were caused by their exposure to chemical waste. She realized that her community known as the Love Canal, was constructed over a pile of twenty-one thousand tons of chemical waste. Despite her lack of prior expertise, Gibbs was able to rally people in her neighborhood to form the Love-Canal Home-owners Association. She successfully organized the movement against local, state, and federal governments. Over 800 households were evacuated and Love Canal cleanup began after years of struggle. Lois Gibbs became famous through national press coverage. Her work also led to the creation of "Superfund," which is used by the US Environmental Protection Agency to find and clean up dangerous sites all over the country42,44.

Marina Silva is an Amazonian Rainforest warrior from Brazil. She collaborated with Chico Mendes and spearheaded campaigns in the 1980s to end the government's exploitation of the rainforest. She became a politician and advocated for sustainable development, environmental conservation, and social justice. From 2004 to 2007, when she was in office, deforestation dropped by 59%. Ms. Silva has spent her whole life fighting for social justice. She fought against forcing indigenous people off their traditional land, and for better access to education, and women's rights. She has also been awarded the Sophie Prize (2009) and the Goldman Environmental Prize (1996)52.

Kinkri Devi led a protest against illegal mining in the mountains in Himachal Pradesh. Quarrying activities spoiled the hills, destroyed the paddy fields, and disrupted the water supply. She vowed to fight the mining interests after seeing the damages. Devi filed a public interest lawsuit against 48 mine owners, accusing them of callous limestone quarrying, supported by People's Action for People in Need, a voluntary organization. The quarry owners disregarded her campaign, claiming she was merely extorting money from them. She waited for a long time but received no response to her lawsuit. She went on a hunger strike for 19 days until the court agreed to hear her case. The hunger strike attracted the attention of both national and international media. In addition to imposing a stay on mining in 1987, a total ban on blasting in the hills was also ordered by the High Court. Furthermore, the Supreme Court rejected the mine owners' appeal in July 1995, further boosting Ms. Devi's popularity53.

Medha Patkar, a well-known environmentalist, led a powerful movement, the Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA), to prevent the construction of dams on the Narmada River in 1985. A multi-crore project, the Sardar Sarovar Dam, was feared to cause the displacement of more than 320,000 people. The rehabilitation of these people was the point of contention in the Save the Narmada Movement. The local people were offered some money and forced to abandon their comfortable, modest dwellings, where they were content to earn a living. The monetary compensation was just a grant-in-aid and in no way adequate to enable a family to purchase property elsewhere. The movement was in support of local people who were being displaced and discriminated against, totally in violation of their human and democratic rights, and also refuted laws protecting the environment. The only compensation to those who were to be impacted by the construction of the dam was an offer of rehabilitation which also worried Medha Patkar. To perform a nonviolent protest, she founded the NBA in 1989 and frequently fasted, and consequently, the NBA raised public awareness54.

Suprabha Seshan is an environmental activist famous for work on conservation of plants, restoration of habitat, and nature education. She is the recipient of the Whitley Award, which is the UK's top environmental award. Her expertise is ex-situ conservation (wherein plants are grown through nursery and gardening techniques), rehabilitation and reforestation followed by natural farming. According to her, plants should not just be for edible purposes but as the creators of environments. Nature is the source of everything of real essence, including wisdom, spirituality, intellect, enjoyment, beauty, art, food, and inspiration, in our lives. It's critical to give back to nature instead of only extracting. The primary task should be to take care of the existing biodiversity. Furthermore, we need to tend to the plants that make up the vegetation and make the environment habitable for humans and other animals. She is credited with restoring endangered lands in high-elevation areas. She is committed to preserving the natural forest and reforesting degraded areas. Her team has painstakingly revitalized a rainforest environment teeming with countless plant species; they call their efforts "ecosystem gardening"55.

Berta Isabel Cáceres Flores was an environmentalist and indigenous rights leader from Honduras (Lenca). She started the Honduran Council of the People’s Indigenous Organizations (COPINH). Berta received the 2015 Goldman Environmental Prize for a campaign wherein she effectively pressured the world's biggest dam construction company (a Chinese state-owned company) to withdraw from the Agua Zarca Dam at the Gualcarque river. Her concern was that the hydropower project of four dams would harm the conventional way of living by restricting their access to food, water, and medical supplies8.

Dayamani Barla is a tribal woman from Jharkhand. She has been working for the upliftment of society, involved in numerous movements and protests, ensuring that the development is not at the expense of Jal, Jungle, and Jameen. She has opposed corruption because the only form of development it would lead to would be unsustainable. In 1995, she organized a protest against the Koel Karo dam's construction at Torpa in Khunti, her birthplace. As a grassroots-level worker, she visits the Adivasis and promotes awareness of the rights guaranteed to them by the Indian Constitution. She is protesting the eviction and land grabbing of the Adivasis in Jharkhand by claiming that separating them from their land will prevent them from breathing. She is a conservationist who has spent nearly four decades working to protect her people's land, forests, and rivers. She is also a journalist, author, and climate change activist. She is the Iron Lady of Jharkhand7.

Menaka Gandhi is an environmentalist and an animal-welfare activist. As the Minister of the Environment, she implemented several significant steps to protect the environment and ecology. She established India's Animal Welfare Ministry and became its first minister. Under her leadership, the members of CPCSEA (Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals) conducted random checks on labs where animals were being used for scientific experiments. CPCSEA took action against those who were cruel to animals. Her initiative mandated that all cosmetic and edible products be labeled as green (for plant-based products) or red (for animal-based products), depending on the ingredients. She spearheaded the largest animal welfare organization People for Animals (Shah, 2015). For her exemplary work on the environment, and animal welfare, she received Dinanath Mangeshkar Aadishakti Puraskar in 200156

Julia Butterfly Hill, an American activist, is well known for her 738-day tree-dwelling protest against the destruction of environmentally valuable forests by engaging in civil disobedience. She aimed to prevent deforestation. For almost two years, Hill lived in a millennial California redwood tree by the name of Luna to bring attention to the environmentally destructive logging practices of a Lumber Company. The tall California Redwood forest trees were rescued owing to her two-year-long protest57

Isatou Ceesay is an activist and social entrepreneur from Gambia who is often called "The Queen of Recycling." She started a recycling movement in the Gambia called "One Plastic Bag." Through this movement, she taught women in Gambia how to turn plastic trash into things like yarn and make small hand-held bags that they could sell and make money. Not only has her project called the N’jau Recycling and Income Generation Group (NRIGG) gotten rid of a lot of trash from within her community, but it also gainfully employs hundreds of women and gives them a steady source of income every month52,58.

Mayilamma, an Indian social activist from a tribal community in Plachimada in Palakkad, Kerala, is the most well-known face of the local community’s fight for water conservation. She played a critical role in the campaign holding Coca-Cola responsible for water scarcity and pollution in Plachimada in Palakkad, Kerala. She launched a satyagraha against the soft drink industry in April 2002. The community compelled the company to shut down its bottling plant in March 2004 under her leadership, for which she received the Stree Shakti Award31.

Vandana Shiva is a renowned environmentalist and campaigner who opposes genetically modified organisms, intellectual property rights, and free trade. In her efforts to secure the future of agricultural systems, she advocates for the use of local seeds and emphasizes the importance of the protection of biodiversity. In her 2004 article "Empowering Women" she argued for a shift in farming practices in India that would be more conducive to female participation. She argues that the world would benefit from having more women involved in environmental efforts. In 1991, Dr. Shiva established Navdanya, to achieve food security in India and to preserve native seed diversity with the support of organic farming and fair trade. The group has set up a total of 124 seed banks across the country. Almost 3,000 different types of rice have been protected in India because of Navdanya59.

Sunita Narain started working on climate change in the 1990s. In 1991, her book, Global warming in an unequal world: A case of environmental colonialism, played a crucial role in affirming the equity principle in the climate change convention. In the year 2005, she received the Padma Shri award. She is known for her work on rainwater harvesting, for which she received the Stockholm Water Prize. She worked with the government of India in formulating new policies for water management She is the director-general of the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), and the editor of "Down to Earth”. In 2005, the Tiger Task Force was set up by the Prime Minister of India following the decline in the tiger population in Sariska. The task force was headed by Sunita Narain. She was a member of the Council for Climate Change and the National Ganga River Basin Authority. Her research interests include local democracy (forests) and global democracy (climate change). Dr. Narain plays an active role in policy formulation on issues of environment and development in India and globally. Her work on air and industrial pollution, water, and waste management resulted in an understanding that viable and sustainable technologies are needed in countries where achieving equitable and sustainable growth are challenging60.

Radha Bhatt started the Uttarakhand Nadi Bachao Abhiyan in 2008 to stop the construction of several hydroelectric projects that would have disrupted the flow of the Ganges and that of the majority of its tributaries in the Himalayan state's fragile, heavily deforested ecology. She promoted women’s empowerment and the Chipko movement. She has taken a lead role in protests against open mining in the Himalayas. Her efforts prevented landslides in more than 50 villages in the area. Radha Bhatt got the Indira Priyadarshini Environment Award for her extraordinary work61

Sylvia Earle spearheaded the movement to explore the ocean. Earle has been underwater for about 6,000 hours and was one of the first to use SCUBA gear. After winning the TED Prize in 2009, Earle started Mission Blue, an association dedicated to establishing MPA (marine protected areas), also called "Hope Spots." Mission Blue aims to protect the oceans from threats, such as climate crisis, pollution, environmental destruction, introduced non-native species, and the dramatic depletion of ocean fish stocks. Earle's ongoing work is enhancing our knowledge of the oceans and helping to devise strategies to protect them62.

Kirti Karanth is the Chief Conservation Scientist at the Centre for Wildlife Studies and has gained recognition as an environmentalist. She contributed to the conservation of the Environment while serving on the editorial boards of the publications such as Conservation Biology, Conservation Letters, and Frontiers in Ecology. Kirti Karanth is the first woman from Asia who was chosen for the Wild Innovator Award in the year 2021 by the Wild Elements Foundation, the organization that works towards identifying solutions for global sustainability and conservation". She is the author of more than 90 scholarly and popular publications63.

Saalumarada Thimmakka (The Green Crusader) and her husband, Bikkala Chikkayya, established a route through rural Bengaluru, Karnataka, lining it with four hundred banyan trees. In addition, she planted 8000 other trees and took care of them. She has earned the titles of silviculturist, environmentalist, and "mother of trees”. Saalumarada Thimmakka participates actively in state and national environmental protection campaigns. She has been an active campaigner in spreading the afforestation drive. In 2014, she established the Saalumarada Thimmakka International Foundation with the primary goal of raising community awareness about the importance of environmental preservation. She was honored with the Padma Shri in 201964, 65.

Jis Sebastian is a women's rights activist and conservation ecologist. She inspired many to value and safeguard orchids by teaching them why doing so can protect entire ecosystems. Orchids are susceptible to climate and environmental changes. A decline in the diversity of orchids indicates the end of a healthy ecosystem. As a Forest ecologist, she is working on endangered epiphytic orchids in the Western Ghats and educating students about forest and plant conservation. According to research, all orchids today are descendants from the dinosaur era during which ecosystems got destroyed, but orchids evolved, diversified, and adapted to the new ecosystems and hence, prospered. They can adapt to new environments and ecosystems that other plants cannot. They are one of the most successful plant families due to their growth, survival, and diversification66.

Dr. Purnima Devi Barman also known as Hargila Baido is a well-known environmentalist. She works for the Assam-based NGO Aaranyak as a conservation biologist. Dr. Purnima received India’s highest civilian award for women, the Nari Shakti award. She started the "Hargila army" which gives women in rural areas a voice as tree protectors. Women were encouraged to join this army, which works to protect Hargila trees and the environment. Her unwavering dedication has given the communities a voice, and by encouraging strong ownership, she has created a model for community conservation67.

Greta Thunberg, a 17-year-old Swedish environmentalist, launched a movement called Fridays for Future, that swept the world by storm. Greta is well-known for her climate change activism. She communicated with the world leaders at the World Economic Forum, the UN Climate Conference, and the US House Select Committee on Climate Crisis. She has motivated young environmental activists worldwide and brought the global climate catastrophe to public notice52,68.

Nguy Thi Khanh observed the negative impacts of mining on the environment and the health of people in her neighborhood. She started the Green Innovation and Growth Centre (Green ID) to promote sustainable energy and development in a nation with rapidly increasing energy demands. She established the Vietnam Sustainable Energy Alliance to unite national and international environmental organizations to promote the transition to sustainable energy sources. She spearheaded the successful efforts to persuade the Vietnamese government to change from a coal-reliant energy plan to a higher share of wind and solar power based renewable energy plan. She received the 2018 Goldman Environmental Prize for her efforts69.

Tulsi Gowda is a veteran environmentalist from Honnali village in Karnataka. She received the prestigious Padma Shri award for her outstanding contributions towards protecting trees and preserving the environment. She has extensive knowledge of various herbs and plants. Tulsi Gowda can identify and obtain seeds from “mother trees” within a forest to regenerate the plant. She is considered an encyclopedia or goddess of forests. She has been engaged in conservation efforts for the past sixty years and has planted over thirty thousand trees70.

Key Policy Actions

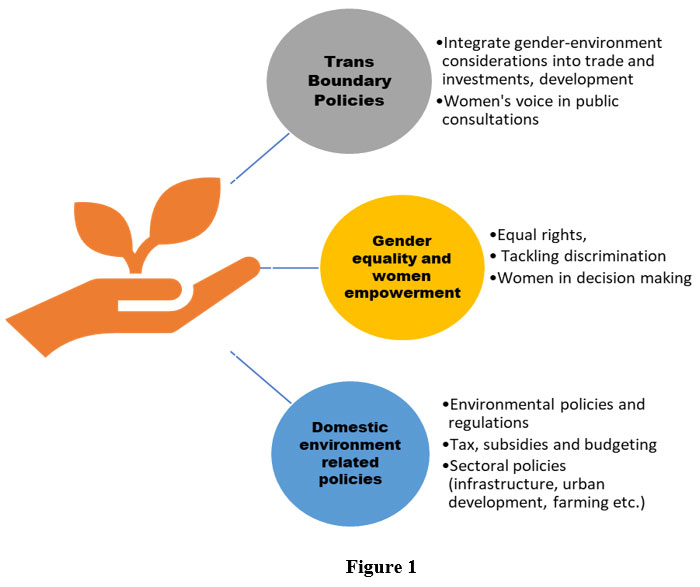

Some of the most important environmental policies and programs, as well as their effects on women, are briefly discussed.

| Figure 1

|

- The National Environment Policy recognizes our society's socioeconomic, political, cultural, and environmental challenges (2006). Through the different forms of occupational security, healthcare system, education, marginalized and vulnerable person empowerment, and gender equality, the fundamental objective of reducing mass poverty is brought into focus. Through diverse expressions of economic security, healthcare system, education, disadvantaged person empowerment, and gender equality, the fundamental objective of reducing mass poverty is addressed.

- Women were supposed to make up 33% of the Vana Sama Rakshana Samitis membership under the National Forest Policy (1988) and the Joint Forest Management (1990s) initiatives. The rationale behind the establishment was that state forest departments could effectively control deforestation if they had negotiated collaborative management agreements with local populations to reforest damaged forests.

- The Biodiversity Act of 2002 emphasizes the significance of women's roles as collaborators and guardians of traditional knowledge. Historically, women have always been responsible for conserving stocks of seed reserves in agricultural communities.

- In India, the government and NGOs are working together to get more women involved in water harvesting projects.

- Efforts to promote renewable energy in rural areas often focus on empowering women by providing them with biogas plants and solar panels for cooking. Those at the bottom of the economic ladder should not be denied access to safe and sustainable sources of energy for the kitchen. Women's contributions to the energy sector should not be overlooked, rather policymakers should actively include them in the process of formulating policies and designing projects71,72.

Conclusion

Environmental conservation is critical since the degradation of the environment is exceedingly damaging to humans, animals, and plants. Damaged ecosystems may take hundreds of years to restore. Natural resource management strategies in homes and communities are affected by environmental degradation. Throughout the world, women oversee the management of forests and agricultural land and the provision of water, food, and fuel. Women are more concerned about environmental issues. Their contribution to biodiversity preservation is significant. Women have a strong relationship with nature and pro-environmental attitudes and beliefs. They have developed a unique set of values on environmental concerns. The perspectives of women towards nature influence how they approach environmental challenges.

Although women actively work to conserve biodiversity, their efforts are not valued. Women's contribution must be acknowledged if the global community is to achieve a sustainable future. The Millennium Development Goals include environmental sustainability and gender equality. The role of women in environment conservation would significantly aid communities in developing the empathy needed to keep individuals' assets and the earth's natural resources balanced. Traditional knowledge, experience, and opinion of women are crucial to making sustainable development policy decisions for maintaining a healthy planet for future generations, as women focus on managing natural resources, biodiversity, and ecosystems. One of the strategies to save the environment may be to promote gender equality by eliminating the plethora of social and economic disadvantages that render women mute and powerless. Greater participation of women must be encouraged to achieve sustainable development and stability.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no known competing financial interests and personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The role of women in agriculture, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA) Working Paper No. 11-02 (2011).

- World Health Organization, Biodiversity and Health (2015). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/biodiversity-and-health. Accessed on December 16, 2022

- Neumayer E and Plümper T, The Gendered Nature of Natural Disasters: The Impact of Catastrophic Events on the Gender Gap in Life Expectancy, 1981–2002, Annals of the Association of American Geographers. (2007); 97(3):551-566, DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x

CrossRef - United Nations Human Rights Special Procedures, Insecure land rights for women threaten progress on gender equality and sustainable development (2017) https://www.ohchr.org/sites/ default/files/ Documents/Issues/Women/WG/Womenslandright.pdf. Accessed on November 15, 2022

- World Health Organization, Social and gender inequalities in environment and health. Fifth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health “Protecting children’s health in a changing environment” (2010) EUR/55934/PB/1 Published January 22, 2010. Accessed on December 10, 2022 https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/76519/Parma_EH_Conf_pb1.pdf

- Mago P and Gunwal I. Role of Women in Environment Conservation (2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3368066 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3368066

CrossRef - Kait K. Sustainable Development: Guiding Principles and Values. Legal Services India (2021). ISBN No:978-81-928510-1-3 http://www.legalservicesindia.com/article/1641/Sustainable-Development,-Guiding-Principles-And-Values.html [Accessed on December 11, 2022]

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2020). Gender and the environment: What are the barriers to gender equality in sustainable ecosystem management? https://www.iucn.org/ news/gender/202001/gender-and-environment-what-are-barriers-gender-equality-sustainable-ecosystem-management [Accessed on December 18, 2022]

- Boserup E, Kanji N, Su Fei Tan & Toulmin C. Woman's Role in Economic Development (2007). DOI https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315065892 e-Book ISBN 9781315065892

CrossRef - Jain S. ’Women and People's Ecological Movement: A Case Study of Women’s ‘Role in the Chipko Movement in Uttar Pradesh,’ Economic and Political Weekly. (1984);19(41):1788-1794

- The Goldman Environmental Prize, The Green Belt Movement: 40 Years of Impact (2018). https://www.goldmanprize.org/blog/green-belt-movement-wangari-maathai/ Published March 21, 2018. Accessed on January 13, 2023

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992, Conferences Environment and sustainable

development. https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 Accessed November 16, 2022 - OECD, Gender and Sustainable Development: Maximising the Economic, Social and Environmental Role of Women. Organization for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD) to the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) (2008). https://www.oecd.org/social/40881538.pdf [Accessed on February 18, 2023]

- Women’s Environment & Development Organization, Advocating at The Un Climate Negotiations Events, UNFCCC (2019). https://wedo.org/advocating-acting-on-the-gap-at-the-un-climate-negotiations/ [Accessed on February 22, 2023]

- Sethi H, “Survival and Democracy: Ecological Struggles in India” in Ponna Wignaraja (ed.), New Social Movements in the South: Empowering the People, New Delhi: Vistaar (1993).

- Alam K & Halder U. K. A pioneer of environmental movements in India: the Bishnoi movement. Journal of Education & Development. (2018) 8(15):283-287.

- Moksha. ‘Bishnoi Communication for Perfect Life, Death and Enlightenment: An Ecological Perspective’, Scientific Journal of International Research. (2014);1(2):91-114

- Down to Earth 2015. Available at https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/a-journey-called-change-49624 [Accessed on September 7, 2022]

- IANS, Odisha Day: Odisha Women Lead Forest Conservation Movement with Undying Resolve as Green Warriors (2021).

- Nitnaware H. How Tribal Women Have Been Protecting 1/3 of Odisha’s Forests, All By Themselves (2021).Available at https://www.thebetterindia.com/255198/odisha-women-tribal-system-kodarapalli-thengapalli-forest-protection-environment-natural-resources-over-exploitation-guard-conservation-him16/ [Accessed on August 23, 2022]

- Bhatt R. Personal Reflections Radha Behn Bhatt Deportate esuli profughe DEP n. 37 / (2018) ISSN 1824 – 4483. https://www.unive.it/pag/fileadmin/user_upload/dipartimenti/DSLCC/documenti/DEP/ numeri/n37/14_Radha_Behn_Bhatt.pdf

- Gottlieb R S. This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment. London: Routledge (1996).

- Ajayan, Silent Valley: 25 years of an Ecological Triumph, (2009), Retrieved From http://www.livemint.com/Home-Page/ZTKhUS56VU5MODk8aYxb2J/Silent-Valley25years-of-an-ecological-triumph.html [Accessed on January 16, 2023]

- Dattatri S. Silent Valley – A People’s Movement That Saved a Forest (2015). https://www.conservationindia.org/case-studies/silent-valley-a-peoples-movement-that-saved-a-forest [Accessed on November 19, 2022]

- Rohith P. The Silent Valley and its discontents: literary environmentalism and the ecological discourse in Kerala (1975-1984). (Doctoral Thesis) University of Hyderabad (2012).

- Klassen C, Indian villagers hug trees (Appiko) to stop deforestation in Karnataka, 1983-1990 (2013). http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/indianvillagers-hug-trees-appiko-stopdeforestation-karnataka-1983-1990 [Accessed on January 22, 2023]

- Mondal P. Appiko Movement in India (2015). http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com/essay/appiko-movement-in-india-usefulnotes/32985/ [Accessed on January 15, 2023]

- Down to Earth 2001. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/gandhamardan-revisited-16391 [Accessed on September 7, 2022]

- The Pioneer Anti-Balco activists who saved G'mardan feted (2021). https://www.dailypioneer.com/2021/state-editions/anti-balco-activists-who-saved-g-mardan-feted.html [Accessed on October 26, 2022]

- Anantharaman L. (2016) https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/Seeing-the-forests-and-the-trees/article14382543.ece [Accessed on February 19, 2023].

- Menon K. P. S. Role of Tribal Women in Sustainable Development. Indian journal of applied research (2016) 6(5):272-274.

- Khadse A., Rosset P. M., Morales H. and Ferguson B. G. Taking agroecology to scale: the Zero Budget Natural Farming peasant movement in Karnataka, India. The Journal of Peasant Studies (2017) 45(1). DOI:10.1080/03066150.2016.1276450

CrossRef - Varun B. Revisiting Deccan Development Society: A Tale of Dalit & Marginalized Women Saving the Environment (2020). https://feminisminindia.com/2020/07/15/deccan-development-society-dalit-marginalised-women-environment/ [Accessed on October 12, 2022]

- Shiva V, Barker D. and Lokhart C. The GMO Emperor has no Clothe. A Global Citizens Report on the State of GMOs - False Promises, Failed Technologies. Synthesis Report Published by Navdanya International (2011).

- Nakhoda Z. Narmada Bachao Andolan (NBA) Forces End of World Bank Funding of Sardar Sarovar Dam, India, 1985-1993 (2010). http://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/narmada-bachao-andolan-nba-forces-endworldbank-funding-sardar-sarovar-dam-india-1985-1993 [Accessed on December 28, 2022]

- Roy A. The Greater Common Good (1999). www.narmada.org/gcg/gcg.html [Accessed on January 30, 2023]

- Mathur et al, Biodiversity Conservation of Plants: The Role of Ethnic and Indigenous Populations. Annals of Forest Research (2022) 65(1):5613-5656.

- Conis E. "Beyond Silent Spring: An Alternate History of DDT". Distillations (2017) 2 (4):16–23.

- Paull, J.The Rachel Carson Letters and the Making of Silent Spring. SAGE Open (2013) 3(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013494861

CrossRef - McGirk T. The Elephant Princess Independent (1995). https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/the-elephant-princess-1617625.html [Accessed on December 10, 2022]

- Karan P. Environmental Movements in India. Geological Review (1994);84(1): 32-41.

CrossRef - Lakshmi C. S. Lessons from the Mountains: The Story of Gaura Devi. The Hindu (2000). http://uttarakhand.org/2000/05/hindu-lessons-from-the-mountains-the-story-of-gaura-devi/ [Accessed on February 5, 2023]

- Mehta M, The Invisible Female: The Women of the UP Hills. Himal (1991);13-15.

- Rawat, R. Women of Uttarakhand: On the Frontier of the Environmental Struggle. Ursus (1996);7(1): 8-13.

- Haberman D. River of love in an age of pollution: the Yamuna River of northern India. University of California Press. (2006). p. 69. ISBN 0520247892.

CrossRef - Sontheimer S. Women and the Environment: A Reader: Crisis and Development in the Third World. London: Earthscan Publications. (1991) p. 172. ISBN 1853831115

- Boyer-Rechlin and Bethany. "Women in Forestry: A Study of Kenya's Green Belt Movement and Nepal's Community Forestry Program". Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research (2010); 25:69–72. doi:10.1080/02827581.2010.506768.

CrossRef - Musila G. Wangari Maathai's Registers of freedom. Grace A. Musila. Cape Town: HSRC Press. (2020). ISBN 978-0-7969-2574-9.

- Muthuki J. "Challenging patriarchal structures: Wangari Maathai and the Green Belt Movement in Kenya". Agenda (2006); 20(69):83–91. doi:10.1080/10130950.2006.9674752

CrossRef - Schell E. E. "Transnational Environmental Justice Rhetorics and the Green Belt Movement: Wangari Muta Maathai's Ecological Rhetorics and Literacies". JAC (2013);33 (3/4):585–613. ISSN 2162-5190. JSTOR 4385-4569

- Shaji K. A. Sugathakumari: A poet who pioneered environmentalism in a state that never prioritized conservation (2020) https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/environment/sugathakumari-a-poet-who-pioneered-environmentalism-in-a-state-that-never-prioritised-conservation-74779 [Accessed on January 13, 2023]

- Barth N. 10 Woman Environmentalists You Should Know About, 2020. https://greenpop.org/10-woman-environmentalists-you-should-know-about/ [Accessed on December 7,2022]

- Salam S. Kinkri Devi: An Inimitable Voice in Environmental Activism (2022). https://feminisminindia.com/2022/01/14/kinkri-devi-an-inimitable-voice-in-environmental-activism/ [Accessed on December16, 2023]

- Patkar M (ed.). River Linking: A Millennium Folly. National Alliance of People’s Movements & Initiatives: Mumbai, India (2004)

- Seshan S. Suprabha Seshan Educationist, forest custodian and earth doctor (2022). https://www.sanctuarynaturefoundation.org/award/suprabha-seshan [Accessed on November 29, 2022]

- https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/indian-parliament/maneka-sanjay-gandhi [Accessed on January 21, 2023]

- Curtius M. "Tree-Sitter Takes Protest to New Heights in Old Growth: Activist lives in redwood owned by lumber company in dispute over logging Humboldt County forest". Los Angeles Times (1998). https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-oct-22-mn-35101-story.html [Accessed on January 1, 2023]

- Webster M. "How a small African recycling project tackles a mountainous rubbish problem". The Guardian (2014) ISSN 0261-3077

- Doerr E. Dr. Vandana Shiva's Decades-Long Environmental Activism is Rooted in Health of All Beings. University of California Global Health Institute (2022). https://ucghi.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/dr-vandana-shivas-decades-long-environmental-activism-rooted-health-of-all-beings [Accessed on November 4, 2022]

- Adlakha N. There are no 10 ways to save the planet’: Sunita Narain (2020). https://www.thehindu.com/society/there-are-no-10-ways-to-save-the-planet-sunita-narain/article33362773.ece [Accessed on December 12, 2022]

- http://wikipeacewomen.org/wpworg/en/?page_id=2388 [Accessed on December 29, 2022]

- Rafferty J. P. Sylvia Earle. Encyclopedia Britannica (2022). https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sylvia-Earle [Accessed on January 6, 2023]

- Bagchi A, "Wildlife Conservation Scientist Dr. Krithi Karanth Wins 2019 Women of Discovery Award", (2018).

- Chaudhary S, Meet 110-Yr-Old Environmentalist Who Planted Over 8,000 Trees, Took Care of Them As Mother Writer: ENVIRONMENT The Logical Indian Crew, (2022). https://thelogicalindian.com/environment/saalumarada-thimmakka-35622

- Das R, “How 107-Year-Old Thimakka Convinced Karnataka CM To Not Axe Trees". She The People TV (2019).

- Dixit M, Earth Day: Ecologist Jis Sebastian on How Orchids Act as Climate Indicator, Importance of Agro-Ecosystems, and More. ENVIRONMENT (2021). https://weather.com/en-IN/india/environment/news/2021-04-22-ecologist-jis-sebastian-on-how-orchids-act-as-climate-indicator [Accessed on February 1, 2023]

- Rhodes C. "A Biologist, an Outlandish Stork and the Army of Women Trying to Save It". The New York Times (2021). ISSN 0362-4331

- Weise E. “How dare you?' Read Greta Thunberg's emotional climate change speech to UN and world leaders”. USA TODAY (2019). https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2019/09/23/greta-thunberg-tells-un-summit-youth-not-forgive-climate-inaction/2421335001/ [Accessed on February 11, 2023]

- Wee Sui-Lee. "She Spoke Out Against Vietnam's Plans for Coal. Then She Was Arrested". The New York Times (2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/17/world/asia/nguy-thi-khanh-environmental-activist-arrested.html [Accessed on February 22, 2023]

- Yasir S. “Magic in Her Hands.' The Woman Bringing India's Forests Back to Life”. The New York Times (2022) ISSN 0362-4331

- Agarwal B. Conceptualizing environmental collective action: Why gender matters, (2000).

CrossRef - Agarwal B. Gender and Green Governance: The Political Economy of Women's Presence, (2010).

CrossRef