Measuring Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility: A Synthesis of Constructs and Measurement Scale Items

K. M. R. Taufique1 * , C. B. Siwar1 , B. A. Talib2 and Norshamliza Chamhuri2

1

Institute for Environment and Development,

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia,

Bangi,

43600

Selangor

Malaysia

2

Faculty of Economics and Management,

Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia,

Bangi,

43600

Selangor

Malaysia

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.9.1.04

It is universal that central to all production is consumption. Without proper management, production along with consumption is likely to be the main sources of environmental problems. This very reality calls for consumers to be environmentally responsible in their consumption behavior. The objective of this paper is to prepare a synthesis of all the possible factors and measurement scale items to be used for assessing consumers’ environmental responsibility. For making such synthesis, all major works done on the field have been thoroughly reviewed.The paper comes up with a total of six parameters that include knowledge & awareness, attitude, green consumer value, emotional affinity toward nature, willingness to act and environment related past behavior. These tentative, yet inclusive set of parameters are thought to be useful for guiding the designing of large scale future empirical researches for developing a dependable inclusive set of parameters to test consumer’ environmental responsibility. A conceptual model and possible measurement items are proposed for further empirical research.

Copy the following to cite this article:

Taufique K. M. R, Siwar C. B, Talib B. A, Chamhuri N. Measuring Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility: A Synthesis of Constructs and Measurement Scale Items. Curr World Environ 2014;9(1) DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.9.1.04

Copy the following to cite this URL:

Taufique K. M. R, Siwar C. B, Talib B. A, Chamhuri N. Measuring Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility: A Synthesis of Constructs and Measurement Scale Items. Curr World Environ 2014;9(1). Available from: http://www.cwejournal.org/?p=5961

Download article (pdf) Citation Manager Publish History

Select type of program for download

| Endnote EndNote format (Mac & Win) | |

| Reference Manager Ris format (Win only) | |

| Procite Ris format (Win only) | |

| Medlars Format | |

| RefWorks Format RefWorks format (Mac & Win) | |

| BibTex Format BibTex format (Mac & Win) |

Article Publishing History

| Received: | 2014-01-27 |

|---|---|

| Accepted: | 2014-03-24 |

Introduction

Consumption is considered to be central to all production. It is used as an indicator to measure the well-being of individuals and household and to improve the quality of life (Magrabi, 1991). However, without proper management, production along with consumption is the main sources of environmental problems (Haronet al., 2005). The reason for this is that the by-products of most consumption are pollution and a fall in the usefulness of energy materials for future consumption (Trott, 1997). Conclusions of many studies have argued that irresponsible consumption behavior is responsible for a significant part of environmental deterioration. Tuna and Özkoçak (2012) suggest that unconscious usage of natural resources for the requirements of humanity and inconsiderate consumption habits of the people have led to irreversible environmental destructions. They further argue that more energy-consuming human activities aiming at satisfying the so-called “well-being” and “comfort” of humanity have contributed to the gradual depletion of energy resources. Miran et al. (2008) claim that it is likely that our planet and all its inhabitants are today threatened by a potential global ecological crisis.

The overuse of nature resources for human purposes and its long term adverse impact made us recognize the human responsibility towards nature. One facet of this recognition is evidenced in the development of eco-friendly consumption patterns among consumers. One study (Grunert, 1993) reported that about 40 percent of environmental degradation has been accounted for by the consumption activities of private household level.

It is thus well evidenced and believed that consumption and consumer behavior at household level are, by and large, responsible for environmental degradation. Accordingly, along with other governing bodies, consumers need to be involved in the journey to environmentally sustainable consumption behavior in order for an economy to grow “green”. The starting point for such journey with consumers is to know their present status regarding their understanding of the issue and how environmentally responsible they are in their consumption behavior. Investigation of this kind is not a straightforward work since the issue is very much latent in nature. The prerequisite for such study calls for an all inclusive set of parameters generated from a comprehensive literature survey.

Materials and Methods

The study is solely based on a comprehensive and systematic review of literature. Several steps have been gone through in searching and selecting the literature for being reviewed. First a very general and broad search was conducted in Google using the key phrases reflecting the topic of the study. Databases such as EBSCO, Emarald, Science Direct, SCOPUS etc. were accessed to search for the relevant research papers. Finally as suggested by Randolph (2009), the references of the retrieved articles were repeatedly searched until a point of saturation was reached. After that the inclusion of the articles was narrowed down to match the focus of this paper following the review guidelines of Hart (1998).

Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility

Consumers’ environmental responsibility refers to consumption activities that benefit, or result in less damage to the environment than substitutable activities (Ebreo, Hershey and Vining, 1999; Pieters, 1991).

Crosby, Gill, and Taylor (1981) defined environmental concern tentatively as a strong positive attitude toward preserving the environment. Later, they defined environmental concern as a general or global attitude with indirect effects on behaviors through behavioral intentions (Gill, Crosby, and Taylor, 1986), based on the work of Van Liere and Dunlap (1981). Zimmer, Stafford and Stafford (1994) supported this definition describing environmental concern as ‘‘a general concept that can refer to feelings about many different green issues.’’ Consumer Environmental Responsibility" is formally defined as "a state in which a person expresses an intention to take action directed toward remediation of environmental problems, acting not as an individual consumer with his/her own economic interests, but through a citizen consumer concept of societal-environmental well-being. Further, this action will be characterized by awareness of environmental problems, knowledge of remedial alternatives best suited for alleviation of the problem, skill in pursuing his or her own chosen action, and possession of a genuine desire to act after having weighed his/her own locus of control and determining that these actions can be meaningful in alleviation of the problem" (Stone et al., 1995, p. 601).

Results and Discussion

After conducting a comprehensive and systematic review of literature, a total of six constructs have been confirmed. The following table (Table 1) summarizes the major constructs for assessing consumers’ environmental responsibility followed by the detailed discussion and argument supported by corresponding literature.

Table 1: Summary of the Constructs for Assessing Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility Illusions

| Construct | References | Key Argument |

| Knowledge and Awareness | Stone et al. (1995); Maloney and Ward (1973); Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera (1986) | - Environmentally responsible consumers must have knowledge |

| and awareness of the environment. | ||

| Attitude | Dunlap & Van Liere( 1978); Jackson (1985); Kinnear, Taylor, & Ahmed (1974); Maloney & Ward (1973); Thompson &Gasteigner (1985). | - Attitude is one of the key elements of an individual’s environmental responsibility. |

| Green Consumer Value | Haws, Winterich, and Naylor (2010) | - Environmentally sustainable consumption behavior is associated with the degree of consumers’ green values. |

| Emotional Affinity toward Nature | Kals, Schumacher,&Montada, 1999; Müller, Kals, &Pansa, 2009; Stern, 2000 | The extent to which a person has an emotional connection to his or her natural environment has impact on individual’s commitment to be responsible for the protection of environment. |

| Willingness to Act | Maloney & Ward (1973); Hines et al. (1986); Berkowitz and Daniels (1964) | - Verbal commitment is a measure for individual’s willingness to act.- Personality factors and social responsibility are also associated with one’s willingness to act. |

| Action Taken/Environment Related Past Behavior | Bennet (1974); Dunlap & Van Liere (1978) | - The engagement in certain behaviors is a must for environmentally responsible consumers |

|

|

Figure 1: Conceptual Model for Environmentally Responsible Consumers |

Knowledge and Awareness

Environmentally responsible consumers must have knowledge and awareness of the environment (Stone et al., 1995; Maloney and Ward, 1973). Level of awareness may not always reflect the amount of information exposed to the individuals. For instance, Arcury (1990) mentions that Americans have been exposed to a plethora of environmental information for years, yet researchers have very little information about how much the public actually knows about the environment. Using a meta-analysis of 128 environmental studies, Hines, Hungerford and Tomera (1986) identified knowledge to be a must among some other variables that are reportedly associated with environmentally responsible behavior. Hines et al. (1986) further propose an environmental behavior model in which the intention to take action is determined to be a combination of other factors including cognitive knowledge, cognitive skills, and personality variables. Cognitive knowledge, in this model, relates to an individual's awareness of existing environmental problems. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that consumers’ level of knowledge and awareness of environmental issues have impact on their degree of responsibility in consumption behavior.

Attitude

A number of authors argued that attitude to be one of the elements that must be present in individuals who put on view of environmental responsibility (Dunlap and Van Liere, 1978; Kinnear, Taylorand Ahmed, 1974; Maloney and Ward, 1973; Thompson andGasteigner, 1985). A new environmental paradigm consisting of an attitude and certain behaviors that would be engaged in by the environmentally concerned individual is necessary (Dunlap and Van Liere, 1978). These authors recognized that ecological problems stemmed in large part from more traditional attitudes and beliefs common in society. They further recommended that man should live in harmony with nature and limits should be imposed on economic growth.

Kinnear et al. (1974) posited that ecological concern was similar in context to environmental responsibility and is composed of two dimensions: (a) an attitude that must express concern for the environment, and (b) a purchasing behavior that must be consistent with maintenance of the environment. They further indicate that the level of ecological concern is a function of both attitudes and behavior. Here attitude refers to attitude towards environmental protection and accordingly the assumption is that consumers who have positive attitude towards environmental protection show more responsibility in their consumption behavior.

Green Consumer Value

Green consumers are defined as those who have a tendency to consider the environmental impact of their purchase and consumption behaviors. As such, consumers with stronger GREEN values (Haws, Winterich and Naylor 2010) will tend to make decisions consistent with environmentally sustainable consumption.

Emotional Affinity toward Nature

Some researchers have begun to explore the individual’s affective influences on environmental concern and behavior (Stern, 2000) that incorporates emotional affinity toward nature (Kals, Schumacher andMontada, 1999; Müller, Kals andPansa, 2009). The authors refer Emotional Affinity toward Nature (EAN) as the extent to which a person has an emotional connection to his or her natural environment. The studies confirmed that EAN explains individual’s commitment to environment to a considerable extent.

Willingness to Act

Environmentally responsible consumers are said to be willing to act for environmental betterment. One measure of the individual’s probable future actions is ‘verbal commitment’ (Maloney and Ward, 1973). A desire to act is further claimed to be closely associated with personality factors such as the individual’s locus of control, his or her attitude, and exhibited personal responsibility (Hines et al., 1986). Berkowitz and Daniels (1964) found that individuals who scored high in social responsibility were more active in church and community affairs and were more willing to contribute their time, money, and energy to these types of activities. This is similar to having a willingness to act. Therefore, it is assumed that consumers’ willingness to act and their environmental responsibility towards consumption behavior are positively correlated.

Action Taken/Environment Related Past Behavior

In addition to having attitude and knowledge, the engagement in certain behaviors is a must for environmentally responsible consumers (Bennet, 1974; Dunlap and Van Liere, 1978). Maloney and Ward (1973) argued that both attitude and knowledge determine the environmentally relevant behaviors that encompass actions that individuals presently pursuing or would be willing to pursue. Hines et al. (1986) emphasized the necessity of ‘actual commitment’ as a measure of an individual’s present behavior. Apparently consumers’ environmental responsibility is said to be reflected in their environment related past behavior.

Consumer Demography

Several studies in the past have attempted to investigate and found that some demographic variables of consumers correlate with environmentally conscious consumption behavior. A review of these studies and their findings in accordance to the select demographic variables are outlined in the following section. This summary is mainly referred to the work of Straughan and Roberts (1999).

Age

Age has been explored by a number of early studies of ecology and green marketing (e.g. Roberts, 1995; 1996b; Roberts and Bacon, 1997; Roper, 1990; 1992; Samdahl and Robertson, 1989; Van Liere and Dunlap, 1981; Zimmer et al., 1994). One general consensus regarding age is that the younger people are likely to be more sensitive to ecological issues. The most common argument for this general consensus is that the people, who grew up in the time of growing concern of environmental issues at some level, are more likely to be sensitive to these issues (Straughan and Roberts, 1999). Ironically, this trend has been found to be reversed in several studies over the last two decades (D’Souza et al., 2007; Jain andKaur, 2006; Roberts, 1996a, 1996b; Samdahl and Robertson, 1989). In fact, like other demographic variables, the findings of the relationship with age and green consumer behavior are not identical. Some studies explored that the relationship between age and green behavior is non-significant (e.g. Roper, 1990; 1992) whereas others revealed the relationship to be significant and negatively correlated (e.g. Van Liere and Dunlap, 1981; Zimmer et al., 1994). Yet some studies found the relationship to be significant, but positively correlated (e.g. Roberts, 1996a; Samdahl and Robertson, 1989).

Sex

As is the case of age, the studies on the impact of gender on green behavior have not come to be conclusive yet. Straughan and Roberts (1999) argue that women are more likely than men to hold attitudes consistent with the green movement due to the development of unique sex roles, skills, and attitudes. Eagly (1987) justifies this inclination of women as their careful consideration of the impact of their actions on others which result from social development and sex role differences. Arcury (1990) suggested that an individual's gender may be a factor in the amount of environmental knowledge he or she possesses as well as the amount of concern the individual displays for the environment.

Income

Environmental sensitivity is generally believed to be positively related to income (Straughan and Roberts, 1999). The authors argue that generally people with higher income can afford the green products which are usually higher in price than the price of conventional products. Income has been considered as one of the predictors of ecologically conscious behavior in several early studies (e.g. Newell and Green, 1997; Roberts, 1995; 1996b; Roberts and Bacon, 1997; Roper, 1990; 1992; Samdahl and Robertson, 1989; Van Liere and Dunlap, 1981; Zimmer et al., 1994). However, few studies found the negative relationship between income and environmental concern (e.g. Roberts, 1996a; Samdahl and Robertson, 1989).

|

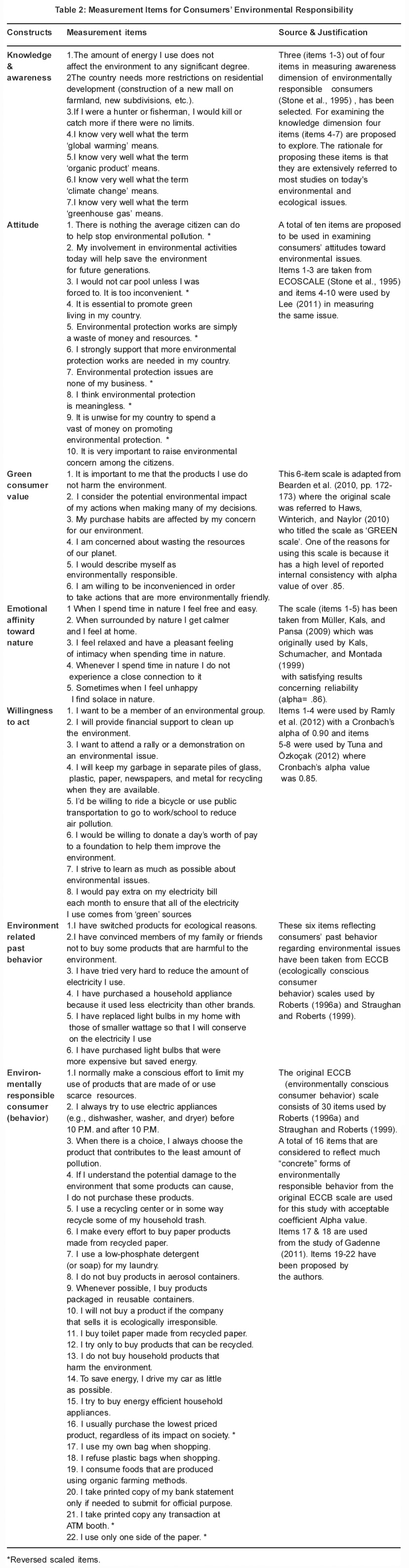

Table 2: Measurement Items for Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility Click here to view table |

Arcury T. A. Environmental attitudes and environmental knowledge, Human Organization, 49, 300-304 (1990).

Education

Level of education is considered to be linked to environmental attitude and behavior (e.g. Newell and Green, 1997; Roberts, 1995; 1996b; Roberts and Bacon, 1997; Roper, 1990; 1992; Samdahl and Robertson, 1989; Schwartz and Miller, 1991; Zimmer et al., 1994). Most of the studies agreed that education is expected to be positively correlated with environmental concerns and behavior (Straughan and Roberts, 1999). While most of the studies come up with positive correlation between education and environmental issues, Samdahl and Robertson (1989) found the opposite, that education was negatively correlated with environmental attitudes.

Proposed Conceptual Model for Environmentally Responsible Consumers

The following figure (Figure1) displays the proposed conceptual framework representing the possible constructs for measuring consumers’ environmental responsibility. In addition to the selected six constructs, selected consumer demographics are proposed to be incorporated in the model to investigate any mediating or moderating impact on consumers’ environmental responsibility.

Items for Measuring the Constructs

A comprehensive literature review has been conducted for compiling a reliable set of scale items for measuring the constructs and testing the proposed model. The following table summarizes the scale items with their corresponding constructs and references.

Acknowledgment

This study was conducted with the funding support from HiCOE project at Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), UKM (XX-05-2012). The authors would like to thank the funding body for supporting the study. The authors also would like to thank the research scholars for their research works that have been used in this study as the sources of data.

References

- Bearden W. O., Netemeyer R. G. and Haws K. L. Handbook of Marketing Scales: Multi-Item Measures for Marketing and Consumer Behavior Research. 3rd Edition. SAGE Publications, 168 – 171 (2011).

- Bennet D. B. Evaluating environmental education programs. In J. A. Swain & W. B. Stapp (Eds.), Environmental Education (pp. 113-164). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (1974).

- Berkowitz L., and Daniels L. R. Affecting the salience of the social responsibility norms. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 68, 275-281. (1964).

- Crosby L. A., Gill J. D. and Taylor J. R., Consumer/voter behavior in the passage of the Michigan Container Law, Journal of Marketing, 45, 19–32 (Spring 1981).

- D’Souza C., Taghian M., Lamb P. and Peretiatkos R. Green decisions: demographics and consumer understanding of environmental labels, International Journal of Consumer Studies 31(4), 371 (2007).

- Dunlap R. E. and Van Liere K. D. The new environmental paradigm, Journal of Environmental Education, 9, 10-19 (1978).

- Eagly A.H., Sex differences in social behavior: a social-role interpretation, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. (1987).

- Ebreo A., Hershey J. and Vining J. Reducing solid waste: linking recycling to environmentally responsible consumerism, Environment and Behaviour, 31, 107–134 (1999).

- Gadenne D., Sharma B., Kerr D. and Smith T. The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours, Energy Policy, 39, 7684–7694 (2011).

- Gill J. D., Crosby L. A. and Taylor J. R., Ecological concern, attitudes, and social norms in voting behavior, Public Opinion Quarterly, 50, 537–554 (1986).

- Grunert S. C., What’s green about green consumers besides their environmental concern? 22nd Annual Conference of the European Marketing Academy, 2. (1993).

- Haron S. A., Paim L. and Yahaya N. Towards sustainable consumption: an examination of environmental knowledge among Malaysians, International Journal of Consumer Studies, 29(5), 426-436 (2005).

- Hart C., Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination, Sage (1998).

- Haws K. L., Karen P. W. and Rebecca W. N., Seeing the world through green-tinted glasses: motivated reasoning and consumer response to environmentally friendly products, Working Paper, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX77843 (2010).

- Hines J. M., Hungerford H. R. and Tomera A. N., Analysis of research on responsible environmental behavior: a meta-analysis, Journal of Environmental Education, 18,1-8 (1986).

- Jain S. and Kaur G. Role of socio-demographics in segmenting and profiling green consumers: an exploratory study of consumers in India, Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 18(3), 107-117 (2006).

- Kals E., Schumacher D. and Montada L. Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature, Environment and Behavior, 31, 178–202 (1999).

- Kinnear T. C., James C. T. and Sahrudin A. A., Ecologically concerned consumers: who are they? Journal of Marketing, 38 (April), 20-24 (1974).

- Lee K. The role of media exposure, social exposure and biospheric value orientation in the environmental attitude-intention-behavior model in adolescents, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31, 301-308 (2011).

- Magrabi F.M., Chung Y.S., Cha S.S. and Yang S., The Economics of Household Consumption. Praeger, New York (1991).

- Maloney M. P. and Ward M. P., Ecology: Let's bear it from the people. American Psychologist, 28, 583-586 (1973)

- Miran B., Günden C. and Sahin A., Awareness to environmental pollution, presented at Southern Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Dallas (2008).

- Müller M.M., Kals E. and Pansa R., Adolescents’ emotional affinity toward nature: a cross-societal study, The Journal of Developmental Processes, 4(1), 59-69 (2009).

- Newell S.J. and Green C.L., Racial differences in consumer environmental concern, The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 31 (1), 53-69 (1997),

- Pieters R.G.M., Changing garbage disposal patterns of consumers: motivations, ability and performance, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 10, 59–77 (1991).

- Ramly Z., Hashim N.H., Yahya W.K. and Mohammad S.A., Environmentally conscious behavior among malaysian consumers: an empirical analysis, JurnalPengurusan, 35, 111-121 (2012).

- Randolph J.J., A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review.Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14, 2 (2009).

- Roberts J.A., Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer behavior: a cluster analytic approach and its implications for marketing, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, Fall, 97-117 (1995).

- Roberts J. A., Green consumers in the 1990s: profile and implications for advertising, Journal of Business Research, 36(3), 217-231 (1996a).

- Roberts J. A., Will the real socially responsible consumer please step forward? Business Horizons 33, 79-83 (1996b).

- Roberts J.A. and Bacon D.R., Exploring the subtle relationships between environmental concern and ecologically conscious consumer behavior, Journal of Business Research, 40 (1), 79-89 (1997).

- Roper Organization, The Environment: Public Attitudes and Individual Behavior, Commissioned by S.C. Johnson and Son, Inc. (1990).

- Roper Organization, Environmental Behavior, North America: Canada, Mexico, United States, Commissioned by S.C. Johnson and Son, Inc. (1992).

- Samdahl D.M. and Robertson R., Social determinants of environmental concern: specification and test of the model, Environment and Behavior, 21 (1), 57-81 (1989).

- Stern P.C., Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior, Journal of Social Issues, 56 ( 3), 407–424 (2000).

- Straughan R.D. and Roberts J.A., Environmental segmentation alternatives: a look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16(6), 558-575 (1999).

- Schwartz J. and Miller T., The earth's best friends, American Demographics, 13 (February), 26-35 (1991).

- Stone G., James H. B., and Cameron M., ECOSCALE: a scale for the measurement of environmentally responsible consumers, Psychology & Marketing, 12, 595-612 (1995).

- Thompson J. C, Jr. and Gasteigner E. L., Environmental attitude survey of university students: 1971-1981, Journal of Environmental Education, 17, 13-22 (1985).

- Trott M., Sustainable Consumption: Issues and Challenges. Indeco Strategic Consulting, Toronto, Canada (1997).

- Tuna Y. and Özkoçak L., The first step to communication with environmentally responsible consumer: measuring environmental consciousness of Turkish consumers, Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 2 (3) (2012).

- Van L. K. and Dunlap R., The social bases of environmental concern: a review of hypotheses, explanations, and empirical evidence, Public Opinion Quarterly, 44 (2), 181-97 (1981).

- Zimmer M.R., Stafford T.F. and Stafford M.R., Green issues: dimensions of environmental concern, Journal of Business Research, 30 (1), 63-74 (1994).